AMBER — En route to measure the proton radius

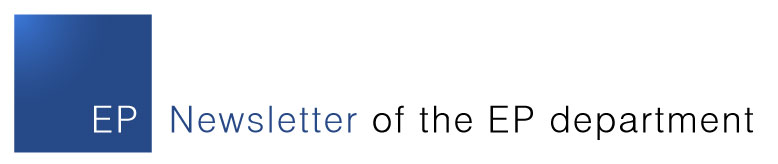

After months of excitement and almost continuous, frenetic activity since August, AMBER’s vast experimental hall — more than 10 m high and stretching over 60 m from the upstream collimators to the far wall — now feels unusually quiet and solitary. Only a few days ago, however, physicists from universities and research institutes across several countries, many of them early-career researchers, were working day and night to bring a brand-new experimental apparatus to life and to record the first beam data.

Seeing the first signals in a new instrument is always a thrill: the passage of a particle through the silicon and scintillating-fibre tracking stations, or the recoil-proton signature in the Time Projection Chamber (TPC), filled with high-pressure hydrogen and serving simultaneously as an active target.

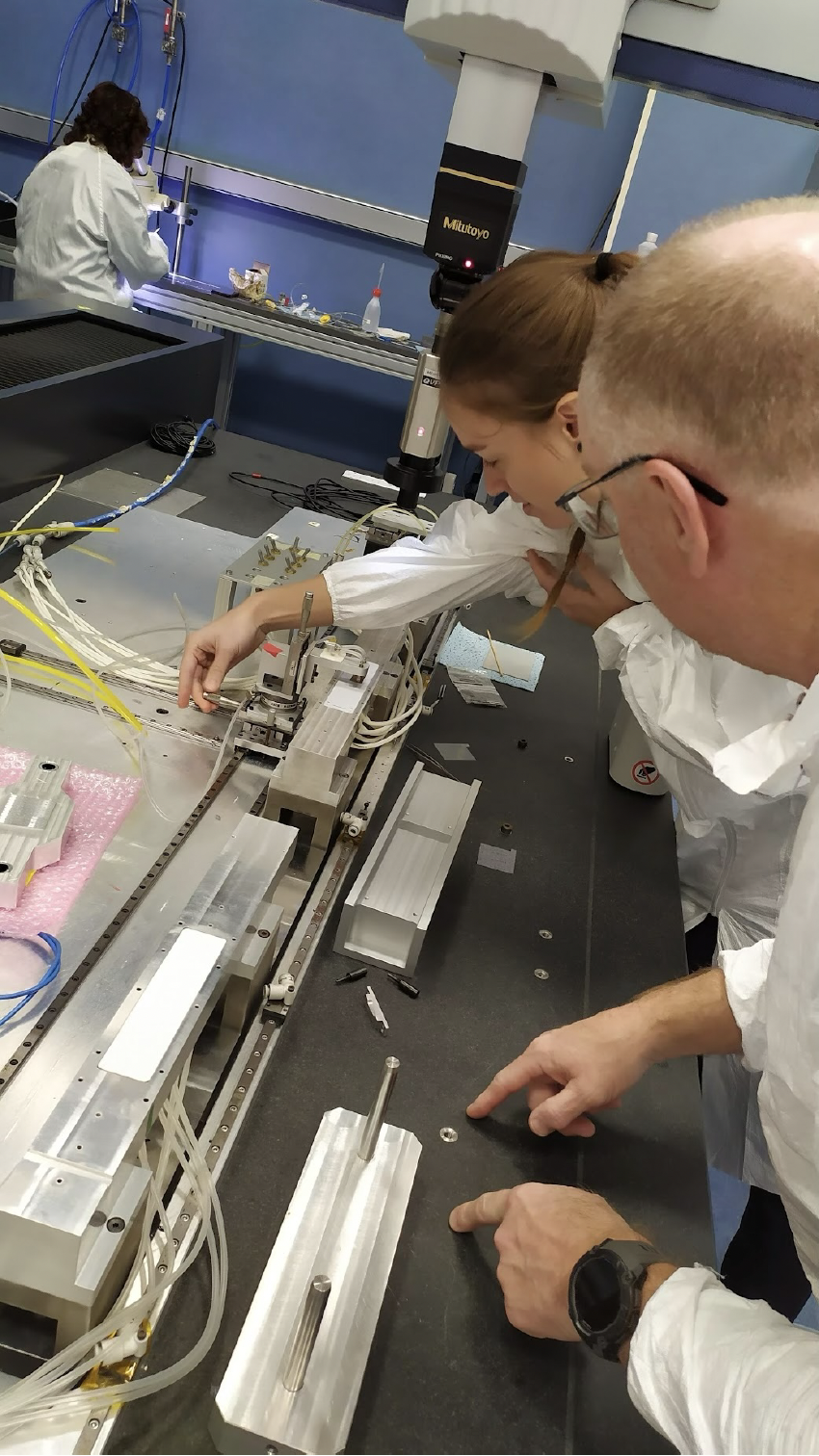

Figure 1: Carlos Garcia Argos during the installation of the Unified Tracking Station downstream of the Time Projection Chamber.

The AMBER 2025 run concluded on 24 November of this year, having met its central goal: commissioning with beam every key element of the setup that will make AMBER’s 2026 proton-radius measurement (PRM) possible.

2 Measuring the proton radius

The spatial distribution of the quark charges inside the proton is a fundamental property of the only stable hadron in our world. As was shown in the pioneering measurements of Robert Hofstadter et al. [1], the mean squared charge radius r2E can be determined from measurements of the electric form factor in elastic scattering of leptons on protons, and by extrapolating it to zero four-momentum transfer squared, Q2. The textbook wisdom of a large radius of rE = 0.88 fm, determined with increasing precision over decades by electron–proton elastic scattering [2], was called into question in 2010 by a high-precision measurement of the Lamb shift in muonic hydrogen [3] that resulted in a small radius of rE = 0.84 fm, with an uncertainty much smaller than the one from electron scattering. This unexpected result was the origin of the so-called Proton Radius Puzzle, which triggered widespread discussions on systematic uncertainties, theoretical corrections, or even new physics.

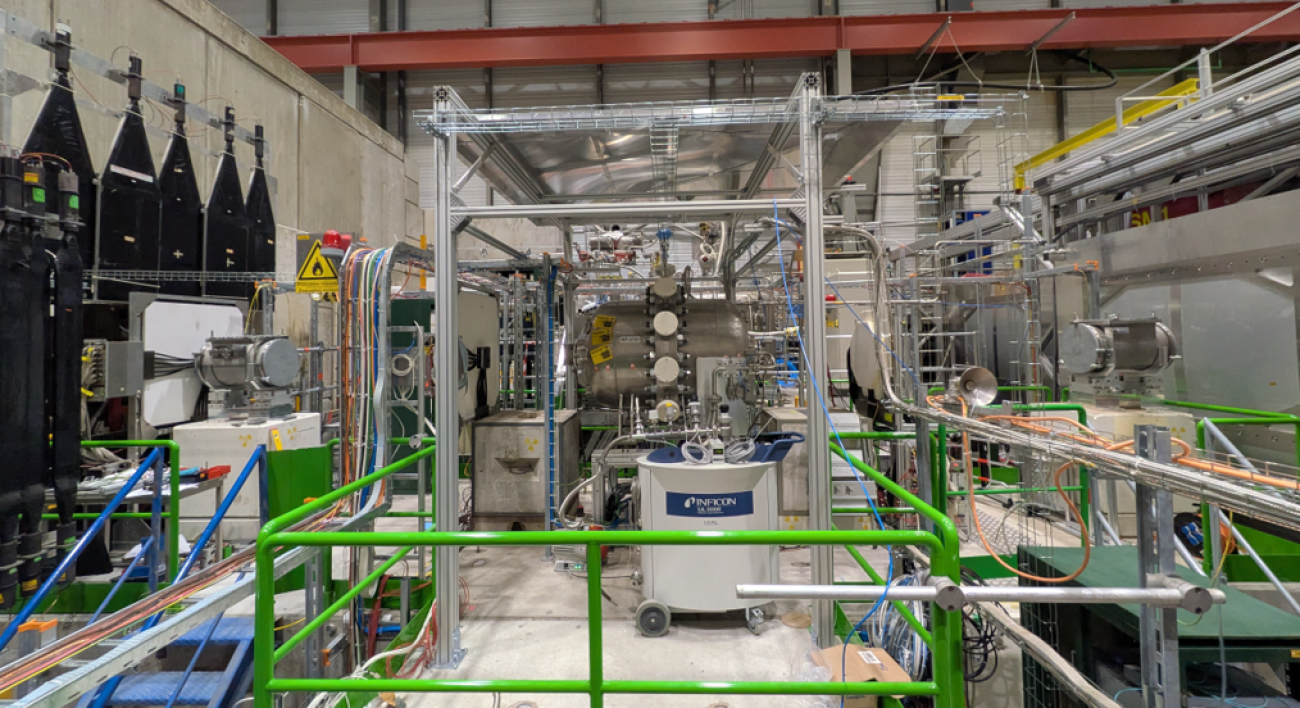

AMBER set out to provide a new and independent precision measurement of this quantity by using high-energy muon elastic scattering on protons rather than low-energy electrons or muons [4, 5]. Such a high-energy muon beam (100 GeV) is available exclusively at the CERN SPS. The advantage of using high-energy muons is that theoretical corrections (and hence also systematic uncertainties) are at least an order of magnitude smaller than for low-energy electrons. The measurement requires the installation of a set of new detectors in the target region of AMBER, as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: AMBER experimental setup for the PRM programme. (Bottom) Complete spectrometer. (Top) Target region with high-pressure TPC as active target and UTS vertex detectors SPD and SFH.

3 The experimental setup at a glance

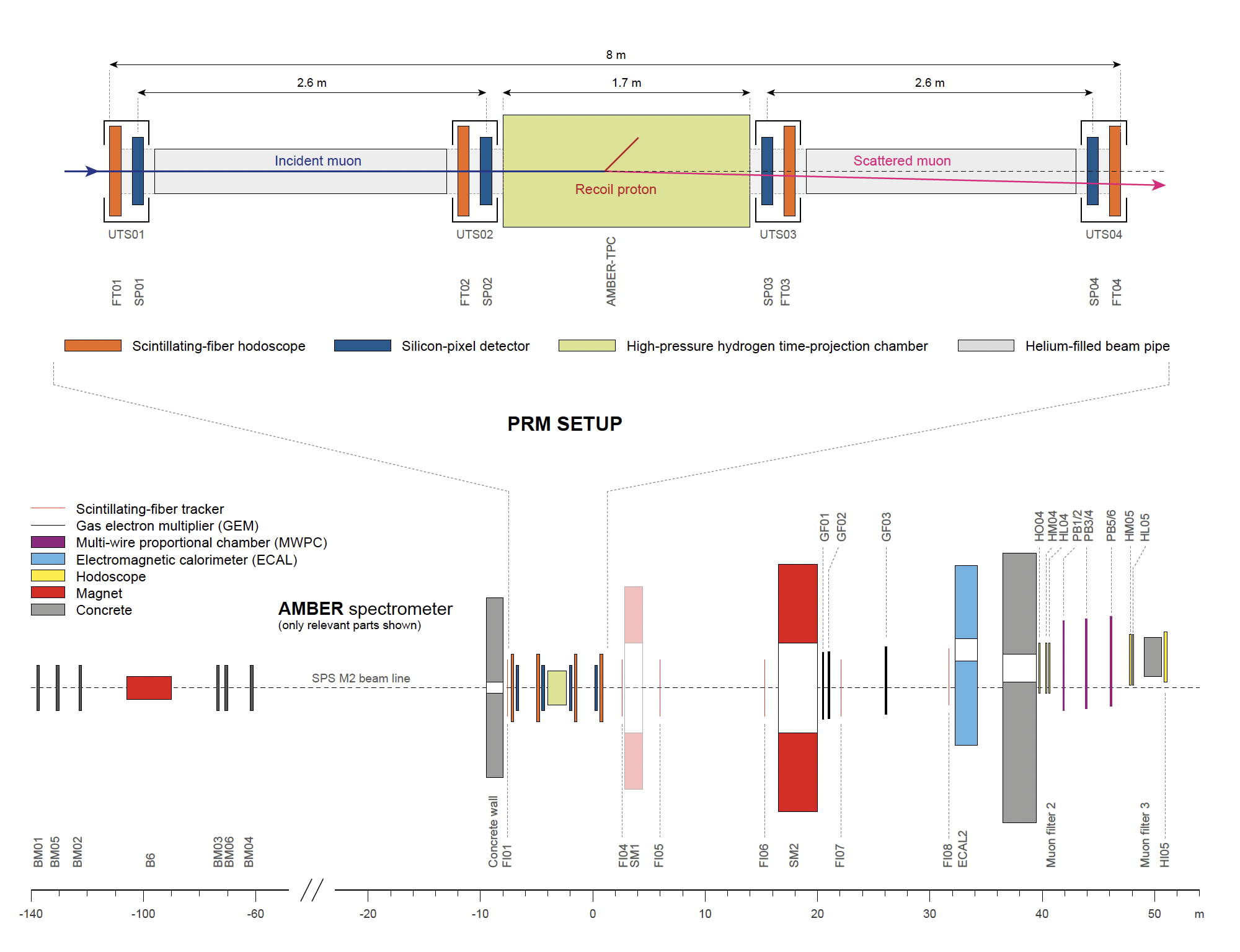

The new setup features cutting-edge silicon-pixel and scintillating-fibre technology for charged-particle tracking and an active target using ultrahigh-purity hydrogen gas at a pressure of 20 bar. The required low momentum transfer between the beam muon and the target proton means that the recoil energies of the proton can be as low as 500 keV. In order to detect the recoil protons, the target medium is used simultaneously as detector: a TPC filled with pure hydrogen. The ionization charge produced by the recoil proton drifts in an electric field of 100 kV/cm over a maximum distance of 40 cm onto a segmented anode plane. No internal charge multiplication is applied in order not to spoil the energy resolution of the instrument: the TPC operates in ionization mode, with the induction gap being separated from the drift region by a Frisch grid.To maximize the luminosity, two TPC cells of 40 cm each are installed in a common high-pressure vessel, with the readout anodes of both cells attached to a central flange, as can be seen in Fig. 3(a). The operation of a detector filled with about 1 m3 of pure hydrogen at 20 bar pressures is a huge challenge, both from a technological and a safety point of view. Every single device in the vicinity of the vessel has to be ATEX-compliant and a countless number of safety interlocks and sensors have been installed in the last months, thanks to the invaluable support of the CERN EP and HSE departments.

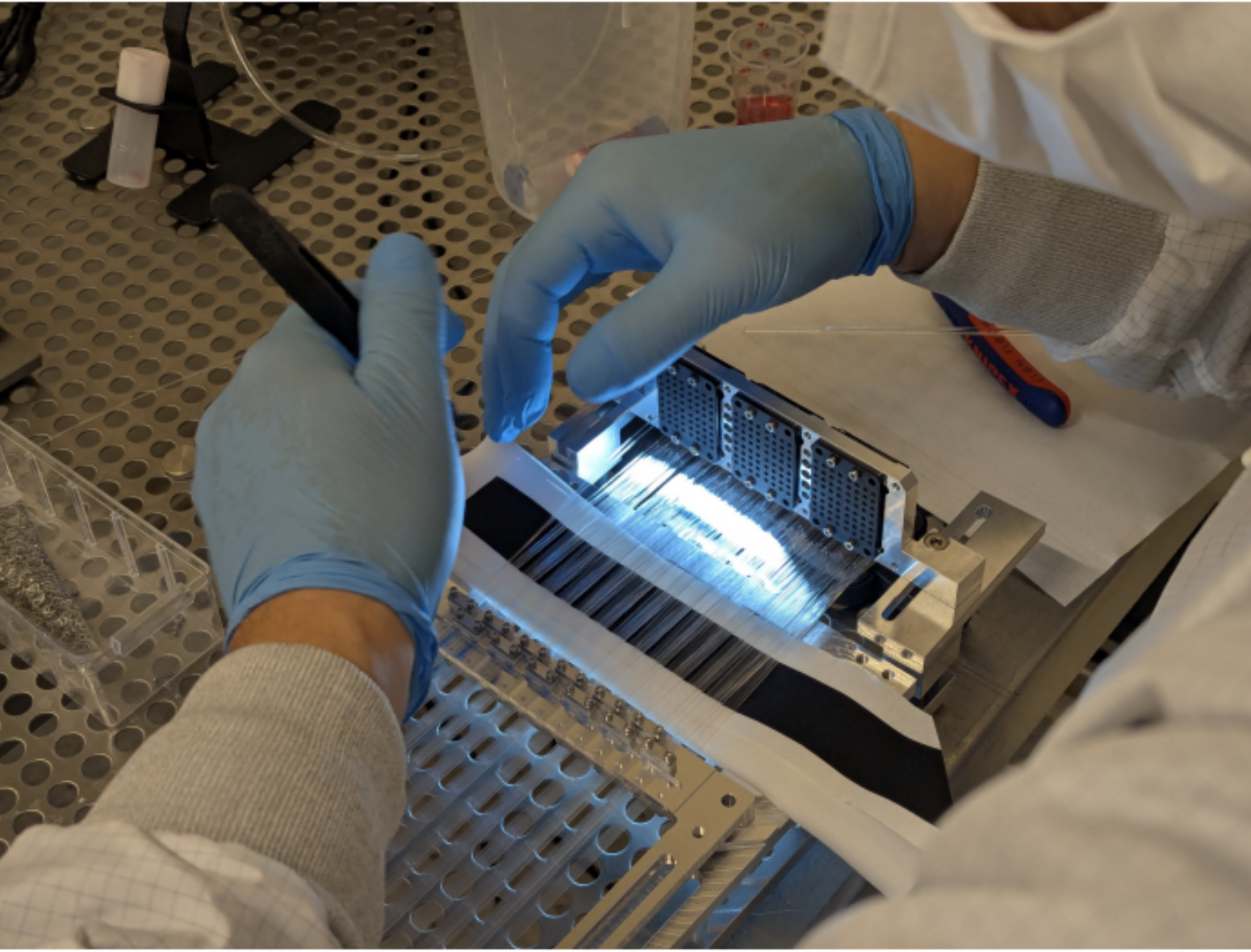

Figure 3: (a) Benjamin Moritz Veit and Vincent Andrieux putting finishing touches on the TPC in the AMBER hall, (b) inner view of a Unified Tracking Station (UTS): an SPD plane in the foreground, mounted in front of an SFH station in the background.

While the energy of the recoil proton, together with the energy of the incoming beam muon, is in principle sufficient to measure the differential cross-section for elastic scattering, the clean selection of elastic-scattering events requires the identification of the scattered muon and the precise determination of the scattering vertex. The first task is taken over by the AMBER spectrometer featuring a dipole magnet, charged-particle tracking using GEM and MWPC detectors, and muon identification.

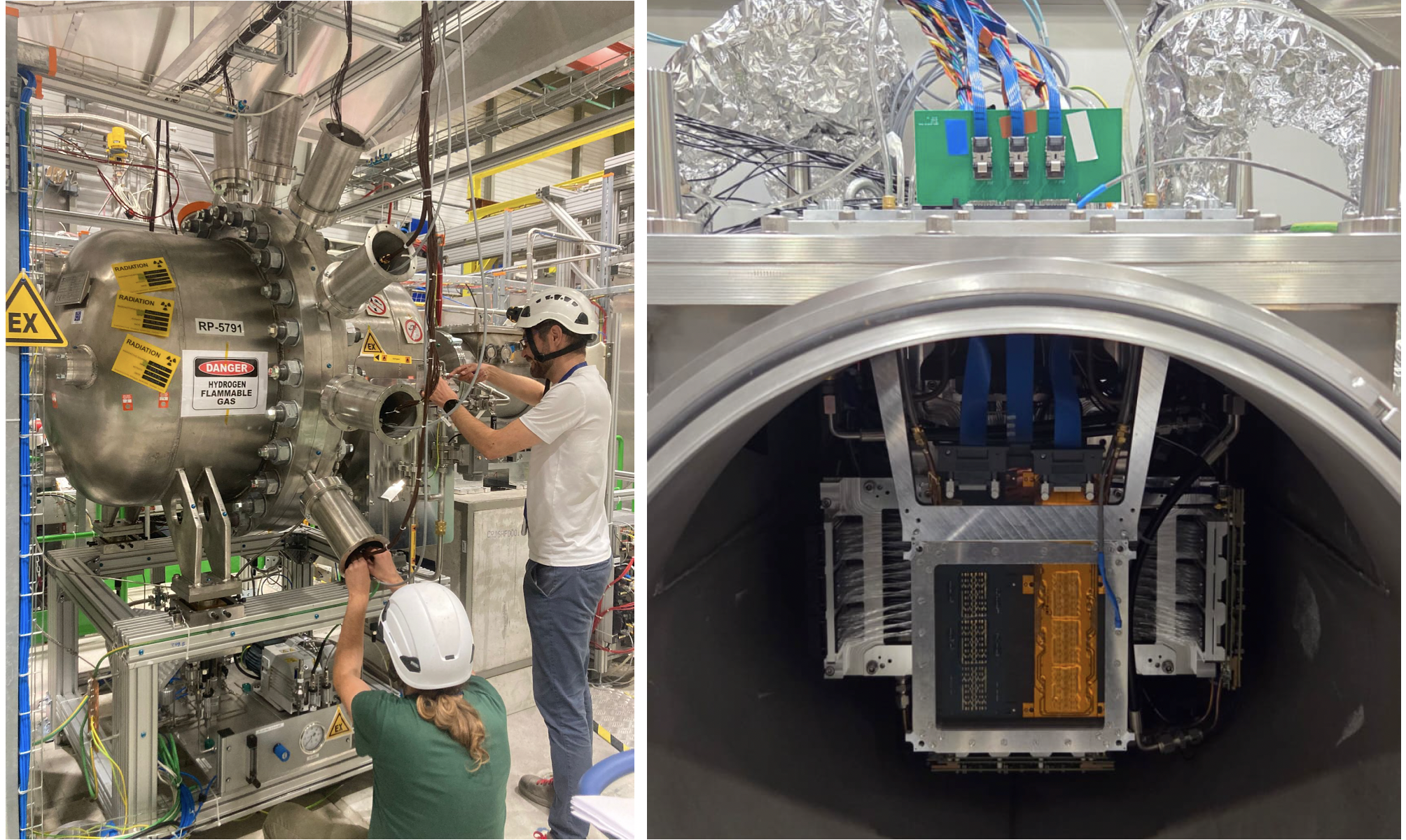

The latter task is performed by a brand-new vertexing system made of four so-called Unified Tracking Stations (UTS) surrounding the TPC, see Fig. 2 (top). Each station comprises three planes of Monolithic Active Pixel Sensors (MAPS) of the ALPIDE type with 8 µm spatial resolution Silicon Pixel Detector (SPD) and four planes (2 × X, 2 × Y) of 0.5 mm thick Scintillating Fiber Hodoscope (SFH), individually read out by SiPM, to resolve hit association ambiguities in the 10 µs long time window of the pixel detector. Figure 3(b) shows a view inside a UTS, while Fig. 4 gives some impressions on the SPD and SFH production.

Finally, the ECAL2 electromagnetic calorimeter, upgraded with a new MSADC readout system, is used to detect photons created in radiative events.

In order to cope with the vastly different time responses of the various detectors and to allow for intelligent event selection, the detector front-end electronics and the data acquisition (DAQ) system were moved from a triggered to a free-streaming system. From the continuous data stream, an online high-level trigger logic selects slices corresponding to detector-specific time windows that are written to disk. From these data, physics events are extracted using a 4-dimensional tracking algorithm.

During the 2025 run, all subsystems anticipated for the 2026 physics run were successfully operated in the full beam environment. Notably, the new triggerless DAQ performed stably and according to design expectations. With the PRM 2025 commissioning complete, the work has now moved from the AMBER hall back to the clean rooms, where the detector planes needed to complete the setup are being produced.

Figure 4: (a) A captured moment from SPD module production at the INFN laboratory in Turin. (b) An SFH plane under production at the TUM laboratory in Munich.

In March 2026, the experiment will return to the beam with the full setup, to deliver the first high-precision μ–p elastic-scattering measurement at AMBER and to add an important new piece to the investigation of the Proton Radius Puzzle.

References

[1] R. W. McAllister and R. Hofstadter. Elastic Scattering of 188-MeV Electrons from the Proton and the α Particle. Phys. Rev., 102:851–856, 1956.

[2] J. C. Bernauer et al. High-precision determination of the electric and magnetic form factors of the proton. Phys. Rev. Lett., 105:242001, 2010.

[3] Randolf Pohl et al. The size of the proton. arXiv:1808.00848 [hep-ex], Nature, 466:213–216, 2010.

[4] B. Adams et al. Letter of Intent: A New QCD facility at the M2 beam line of the CERN SPS (COMPASS++/AMBER). 8 2018, https://arxiv.org/abs/1808.00848

[5] B Adams et al. COMPASS++/AMBER: Proposal for Measurements at the M2 beam line of the CERN SPS Phase-1: 2022-2024. Technical Report CERN-SPSC-2019-022. SPSC-P-360, CERN, Geneva, May 2019.