Frank Wilczek in Conversation: The Beauty of Fundamental Physics

Photo Cretis: Michael Clark

In this wide-ranging interview, Nobel Prize–winning physicist Frank Wilczek reflects on the discoveries that shaped his career and the ideas that continue to orient his work. He recalls his collaboration with David Gross and the emergence of quantum chromodynamics; he turns to the enduring puzzles of the Higgs boson and dark matter, and to the long, patient search for axions.

Moving beyond physics alone, Wilczek considers the role of beauty and symmetry in scientific thought, the shifting balance between theory and experiment, and the promise—along with the limits—of artificial intelligence.

What emerges is a vivid portrait of a scientist whose curiosity has not dimmed with time, and who continues to find, in both nature and human invention, an open invitation to wonder.

Panos Charitos: You’ve spoken fondly about your parents and early environment. Could you reflect on how your family background and upbringing shaped your intellectual curiosity and your path into science?

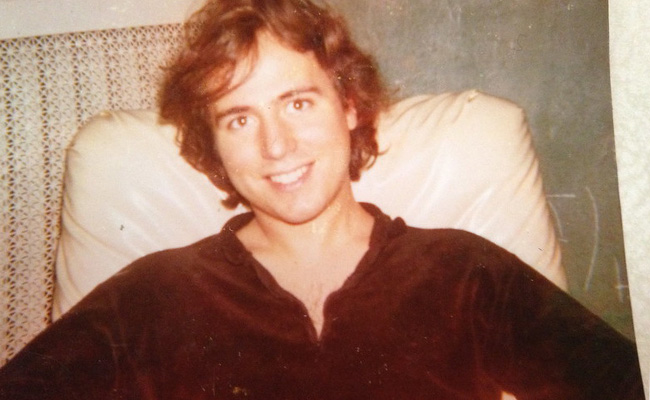

Frank Wilczek: Yes—well, that supermarket story about naming the axion, which I’ve mentioned elsewhere, happened when I was already a young adult. To understand it properly, though, you really have to look further back. My grandparents were refugees—on my father’s side from Poland and Ukraine, and on my mother’s from Italy. They eventually settled on Long Island, where my parents met. My parents were thoroughly American, and English was spoken at home, so it wasn’t an “old-world” household, even though my grandparents themselves very much were.

I grew up in Queens, New York, in a lower-middle-class family. My father hadn’t finished high school; instead, he took equivalency exams and night classes while working as an electronics technician during the heroic era of vacuum tubes. That technical atmosphere at home—radios, televisions, vacuum tubes—had a strong influence on me and did a great deal to stimulate my curiosity.

We weren’t wealthy, but my parents placed a high value on education, and I benefited enormously from New York City’s public schools. My father admired engineers like Edwin Armstrong and was largely self-educated; my mother was intellectually curious and socially engaged. They once gave me a telescope as a joint purchase—I paid for half, my father paid for the other half—and they encouraged me to buy Dover reprints of scientific classics. My father had a clever rule: “Buy any book you like, but if it’s one I approve of, I’ll pay half.” He approved of the Dover books—Weyl, Einstein—which were exactly what I wanted anyway. In that way, they gently steered me toward the best material.

They followed my progress at school closely—report cards and the like—but since I did well, it was never a point of tension.

Wilczek as a high school student in Queens, New York. Courtesy of Frank Wilczek

Panos Charitos: When did you decide to study physics?

Frank Wilczek: In truth, I only made that decision in graduate school. As an undergraduate, I had read Feynman’s Lectures on Physics and believed I understood them—though, in retrospect, I clearly did not. Among the Dover reprints, I worked my way through Hermann Weyl and Einstein; it was challenging, but I gained something valuable from the effort. Even so, at that stage, I still had no clear sense of what I ultimately wanted to pursue.

As an undergraduate, I majored in mathematics because it was easy, didn’t require lab work, and left me room to explore philosophy, mathematical logic, and what we’d now call computer science.

I went to Princeton for graduate school in mathematics, but really under false pretences. I would rather not stay in pure math; it was a holding pattern. For two years, I wandered — seminars, colloquia in physics, biology, philosophy. I wanted to understand the mind at a scientific level. I wasn’t yet a mature scientist.

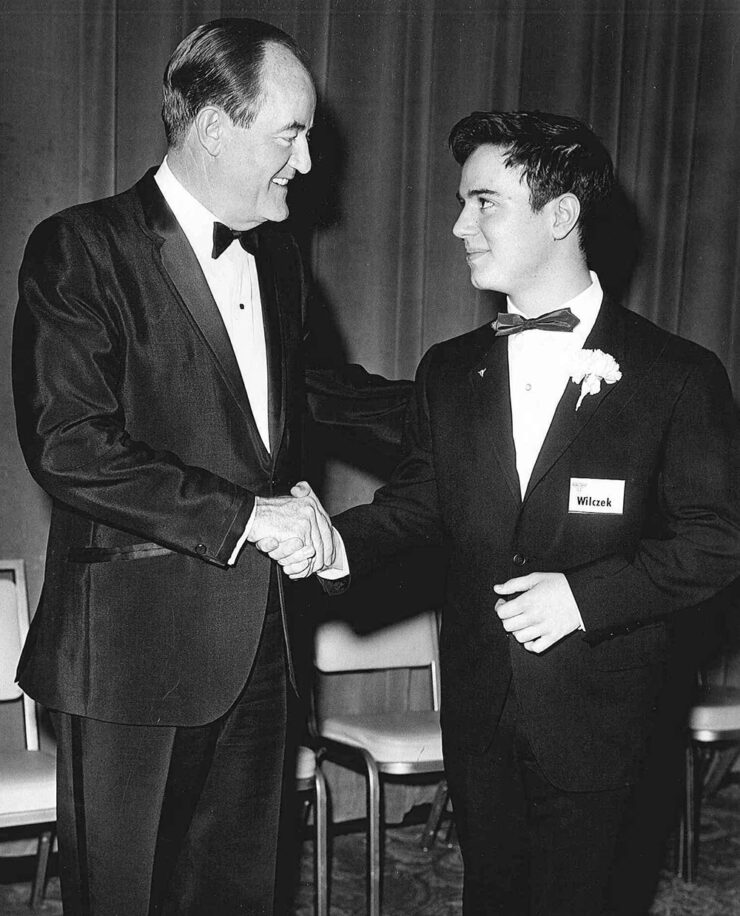

Vice President Hubert Humphrey congratulating Wilczek after his fourth place win at STS in 1967.

But physics in the early 1970s was a particularly dynamic field—important things were happening. And much of that work relied on the mathematics of symmetry, which I loved.

I thought back to Peter Freund’s group theory course at Chicago—it had been a joy. At Princeton, it became clear to me that group theory, local symmetries, and the renormalisation group—what you might call “symmetry at different scales”—were becoming central to the field. Ken Wilson was lecturing on renormalisation and critical phenomena. I didn’t yet understand these ideas in detail, but I had a strong sense that something significant was unfolding.

Then I took David Gross’s course on quantum field theory. His passion was infectious. I began talking to him regularly, and before long I made the transition from mathematics to physics. That was the beginning of everything.

Panos Charitos: In your book "Fundamentals", you say the notion of spin changed your life. Could you reflect on that?

Frank Wilczek: Absolutely. The quantum theory of angular momentum remains, for me, the most profound and beautiful part of science. It provides an exact and surprising bridge between abstract mathematics and very tangible physical reality. You begin with something purely mathematical—the representations of the rotation group—and from that alone you can determine what kinds of particles can exist, what states are possible, and even how matter is organised at its deepest level.

The correspondence between mathematics and the physical world is so precise, so unexpected, and yet so productive that it can feel almost magical. This is not vague philosophy, though it certainly carries philosophical weight. It is computational: it leads to exact predictions that can be tested in the laboratory, and it explains phenomena ranging from the structure of atoms and the periodic table to the very foundations of chemistry.

The concept of spin also opened the door to much more—the way particles transform, the distinction between fermions and bosons, the exclusion principle, superconductivity—all of it flows from this single idea. As a student, realising that one mathematical concept could reach so deeply into the structure of the world was transformative. I felt then, and still feel now, that it captures what is most inspiring about physics: the way deep laws of symmetry do not merely describe the world, but actively shape it.

Panos Charitos: Coming back to your work with David Gross. Can you describe the moment you realised that the strong force gets weaker at shorter distances? How did that insight emerge?

It began as a calculation. At the time, I wasn’t primarily focused on the strong interaction itself; what concerned me most was the internal consistency of quantum field theory.

Landau and others had long worried about what came to be called the Landau ghost: the idea that if a theory is not asymptotically free, its interactions grow uncontrollably at short distances, making the theory inconsistent. This issue had been carefully analysed for Abelian gauge theories, such as quantum electrodynamics, but not for the non-abelian gauge theories that were increasingly looking like candidates for describing the real world—particularly the emerging electroweak theory.

As a graduate student, I was searching for a PhD problem that was both concrete and promising. Studying the short-distance behaviour of non-abelian gauge theories seemed like a natural and important question. It offered a direct way to test whether these theories could make sense at the most fundamental level.

The work was technically demanding. On one side there was gauge invariance; on the other, the renormalisation group; and between them, a great deal of complicated and often messy algebra. For weeks, I struggled to bring these elements together. I worked through the problem in several independent ways, partly out of caution—I didn’t yet trust any single calculation enough to rely on it.

Then one night—late in Jadwin Hall—I remember the moment vividly. After chasing down all these parallel approaches, they finally converged. Methods that should have produced the same result at last did so. And the answer was striking: the theory behaved well at short distances. There was no Landau ghost. In fact, just the opposite—the interaction became weaker the closer you looked. The theory was asymptotically free.

That was the moment when I felt I had something solid—something I could truly believe in.

David Gross already had the renormalisation-group intuition firmly in hand, shaped in large part by Ken Wilson’s lectures. At first, neither of us fully grasped the broader implications of the result. But after a week or two of intense discussion, it became clear that we were looking at an entirely new picture of the strong force. Suddenly, we had a consistent theory of quarks and gluons, along with a clear framework for making experimental predictions.

Once the calculation was secure, everything moved quickly.

Panos Charitos: Did you discuss the discovery with many people?

Frank Wilczek: No—it was a very small circle: David and I, along with a couple of other graduate students, Bill Caswell and Bob Shrock. I also spoke frequently with Sidney Coleman, who pushed me to check the algebra in multiple ways. Once the result had stabilised, he became genuinely enthusiastic—he even discussed it at the Erice summer school. For me, still a student at the time, that was an electrifying experience.

Panos Charitos: The term “asymptotic freedom” is quite poetic. Where did it come from?

Frank Wilczek: That was Sidney Coleman. He had a remarkable gift for language and physics, and he coined the phrase. For physicists, it’s a beautiful term—it captures the essence perfectly: as you probe ever shorter distances, quarks behave as though they are almost free.

For the wider public, though, it’s much less transparent. The word asymptotic doesn’t mean very much unless you’ve spent time with mathematical analysis. On more than one occasion, I’ve been introduced at public events as the discoverer of “asymptomatic freedom”! So the poetry can get lost in translation.

But among physicists, the name stuck immediately, and it shaped how strongly the discovery resonated. The phrase itself conveys something genuinely profound: freedom does not emerge at large distances, as one might intuitively expect, but in the limit as you go deeper and deeper inside matter. It’s a reversal of common sense, distilled into two words. That’s why it’s poetic.

David Gross and Frank Wilczek, when they received the Nobel prize in 2004. Image credit: D Gross.

Panos Charitos: The Nobel Prize came about 30 years after the original papers. How did that long gap between the early breakthrough and the eventual recognition feel to you?

Well, I don’t know for certain, of course, but I can speculate about several reasons that make sense.

One is that the Nobel Committees are inherently conservative—and for good reason. Our theoretical claim was both precise and ambitious: that this was the correct theory of the strong interaction. It wasn’t just a bold idea; it also made very specific predictions. The committee therefore needed to be absolutely confident. They didn’t want to award the prize prematurely and risk being proven wrong later.

The truly decisive experimental confirmation only came with LEP in the 1990s. By that point, quantum chromodynamics was widely accepted within the physics community, but earlier the evidence had not been so airtight that it was beyond dispute. By way of analogy, consider cosmic inflation: it is broadly accepted and strongly supported, yet the evidence remains circumstantial rather than definitive—and the Nobel Committee has not gone there either.

That was one factor. Another, I think, is that our work rested on earlier experimental and theoretical developments that needed to be recognised first. The deep inelastic scattering experiments at SLAC—carried out by Friedman, Kendall, and Taylor—were crucial in opening the door. Their Nobel Prize, awarded in 1990, clearly had to precede ours, even if the delay itself was rather long.

In addition, the work of ’t Hooft and Veltman on the renormalisation of gauge theories was absolutely essential for what we did. Their contribution was recognised with the Nobel Prize in 1999, not long before ours. Once those acknowledgements were in place, the remaining delay was relatively short.

Seen in that light, the timeline makes sense: first the experiments, then the theoretical tools, and finally QCD itself.

![]()

LEP Fest 2000 Science Symposium — F.A. Wilczek delivering the closing presentation on the future of particle physics.

Panos Charitos: At some point, you began to consider what might happen if more than one scalar field were involved in the mechanism responsible for fermion masses—an idea that eventually led you toward the axion.

Frank Wilczek: Yes. I felt that I had the basic structure of the fermion mass–generation mechanism reasonably well understood, at least at a conceptual level. That led me to ask a further question: what changes if more than one scalar field participates?

With a single scalar field, there is limited structure, but introducing multiple scalar fields allows new continuous symmetries to arise. That observation triggered the next step. At the time, instantons and the theta vacuum were central topics at Princeton—recent developments that generated considerable excitement and were widely hoped to explain confinement. Although that particular expectation was not borne out, the mathematical framework was extremely powerful, and I had absorbed it.

I began to explore a model with two scalar fields whose couplings to fermions are arranged differently—for example, one coupling to right-handed up-type quarks and the other to right-handed down-type quarks. If the two scalar fields are rotated with opposite phases, the resulting global symmetry is chiral and anomalous, with the anomaly directly associated with QCD. That immediately implies the existence of a new pseudoscalar mode—very light, not exactly massless, but close to it.

At the time, I viewed this primarily as an interesting theoretical problem: to determine the mass and other properties of such a particle. I was not yet thinking explicitly in terms of the strong CP problem. I was aware of Peccei and Quinn’s work, but I had not studied it carefully, so the idea developed independently, without being placed into that broader context.

Panos Charitos: So at first, you didn’t see it as the solution to the CP problem?

Frank Wilczek: No, not really. I didn’t think of the theta problem as a problem at all. I simply noticed that the symmetry structure was connected to the theta term and could transform it. Very shortly afterwards, I educated myself more thoroughly and began to see the deeper significance.

My initial instinct was that the particle implied by this symmetry would be very light—and that if it existed, we surely would have seen it already. What I hadn’t yet appreciated was how weakly it would couple to ordinary matter, allowing it to evade detection. That’s why I didn’t rush to publish at first, unlike the Higgs–gluon coupling, which I wrote up immediately.

As I worked on calculating its mass, I gave a series of talks at Princeton. Curt Callan attended one of them, and later, when he moved to Harvard, he mentioned my ideas to Steven Weinberg. Weinberg was already thinking along similar lines. To his great credit—given that he was a towering figure in the field, and I was a young researcher—he called me up. We compared notes and quickly realised that we were very much on the same wavelength.

We agreed to publish our papers side by side, and we even agreed on the name. Weinberg had been calling the particle the “Higglet,” while I had been calling it the “axion,” after a laundry detergent—because it “cleaned up” the strong CP problem. Weinberg graciously agreed that axion was the better name, and that is the name that stuck.

The first versions of the axion we proposed were ruled out fairly quickly, mainly on astrophysical grounds. But with relatively modest modifications—shifting from weak-scale to unification-scale symmetry breaking—the axion remained viable. That is where things stand today: it is one of the leading candidates for dark matter.

A few years later, at the 1982 Nuffield conference in Cambridge—a famous meeting organised by Stephen Hawking and Gary Gibbons, where inflation was effectively established—I was asked to give the opening and summary talks. There, I pointed out that in cosmology one should not simply assume that the universe sits in its ground state, as we had done in the original axion papers. One has to ask: how did it get there? That question launched axion cosmology. Together with John Preskill and others, we estimated how much relic axion matter could exist in the universe. That was really the birth of the idea of axions as dark matter.

That collaboration with John Preskill and others helped launch the field. Since then, axions have kept resurfacing throughout my career. I’ve worked on condensed-matter analogues—materials whose equations mimic axion physics—helping to turn this into a thriving subfield. And more recently, I’ve been involved in serious experimental efforts that may finally reach the sensitivity needed to detect them.

Panos Charitos: Looking ahead, what do you see as the Higgs boson’s legacy, and where should future work go?

Frank Wilczek: Like many people, I’ve been both surprised and a little disappointed that the Higgs sector has turned out to be so simple—at least so far. I always thought there was considerable circumstantial evidence—I still do—for low-energy supersymmetry, largely because of gauge-coupling unification. That framework naturally requires at least two Higgs doublets. (For some early arguments along those lines, see Dimopoulos, Raby & Wilczek, 1981, Phys. Rev. D).

Those extra Higgs states may well exist. It could simply be that the LHC doesn’t quite reach the energies needed to bring them into view. But in today’s environment, with tight resources and competing priorities, it’s a complex case to make for new large-scale facilities.

Looking a century ahead, though, I’m more optimistic. With advancing technology, societies are likely to become wealthier and better educated, and more willing to invest in ambitious experiments. When that happens, I think we’ll build the machines capable of revealing—if they exist—the additional worlds that have been hinted at, but not yet discovered.

📌 Side-note for readers: The Higgs boson was discovered at the LHC on 4 July 2012, primarily via gluon–gluon fusion (ggF). The 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics recognised Englert and Higgs for the mechanism confirmed by that discovery. CERNCERNNobelPrize.org. The ggF remains the dominant production channel at the LHC; precision measurements and reviews quantify its leading share relative to VBF and associated modes.

Panos Charitos: In your book “A Beautiful Question”, you write: “Having tasted beauty at the heart of the world, we hunger for more.” . What makes beauty such a reliable compass for you in physics.

Panos Charitos: In your book “A Beautiful Question”, you write: “Having tasted beauty at the heart of the world, we hunger for more.” . What makes beauty such a reliable compass for you in physics.

Frank Wilczek: Absolutely—it has been the keystone of much of my most consequential work.

Take quantum chromodynamics, for example. It is an almost ideal embodiment of mathematical beauty. Gluons are gauge fields—they literally make local symmetry possible—and their properties follow inevitably from that fact. Once you accept asymptotic freedom, the theory that fits our observations becomes essentially unique, and that sense of inevitability is itself a form of beauty.

The same aesthetic reasoning appears in other contexts as well. Consider the axion, which emerged from the search for symmetry within a two-Higgs framework. Despite its complexity, the story illustrates how beauty can guide us when experimental clues are scarce. In modern physics, the sequence often runs in reverse compared with the Newton–Galileo era: we propose theories first and then design experiments to test them.

In this sense, beauty is not merely a matter of taste—it is a form of effectiveness. As I’ve said before, when we describe physical laws as “beautiful,” we usually mean two things: they are wonderfully symmetric and wonderfully productive. Symmetry is change without change—the way a circle remains the same under rotation. That robustness is extraordinarily powerful: once you write down the right symmetry, you get far more out than you initially put in.

This is not confined to abstraction. Ordinary matter, properly understood, embodies remarkable beauty as well. In molecules and ordered materials, atoms act like instruments in a harmonious ensemble, playing together in synchrony. That is why I sometimes like to speak of a modern Music of the Spheres.

Across frontier physics—especially in realms far removed from everyday experience—aesthetic criteria often serve as our most reliable compass. Clean, symmetric, compelling theories guide us while experiments work to catch up. For me, that combination of symmetry, simplicity, and the ineffable sense that things make sense—that you are getting more out than you put in—has been a constant guide to good ideas.

Panos Charitos: There is a verse from the Greek poet Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke: “How can poetry remain beautiful, now that the truth has become ugly?” I wonder whether something similar applies to science today.

Frank Wilczek: Not really—because the truth, at least in fundamental physics, is not ugly. On the contrary, it is very beautiful.

Of course, beauty can take different forms. In something like the Krebs cycle—a dense, intricate network of reactions governing metabolism—the beauty isn’t immediately obvious. It’s like poetry in a foreign language: ornate, difficult, requiring immersion before you begin to sense its elegance. But in physics, especially at the fundamental level, the truth has a clarity that I would never call ugly.

Politics, of course, is another matter. In the political realm, truth is frequently disfigured, as the cadence of daily events reminds us. In physics, however, beauty has long served as a compass—and, so far, it has not led us astray.

Panos Charitos: Do you think physics still has room for elegant laws—or in this era of fragmented models and endless simulations, do we risk losing that compass of beauty?

Frank Wilczek: That’s a real issue, and one I think about often. When you move from the pristine clarity of basic laws to their concrete applications—designing real experiments, simulating messy environments, modelling complex systems—the beauty becomes harder to perceive. The underlying harmony is still there, but it’s veiled.

As I sometimes say, the calculation can never be more beautiful than the answer. If the phenomenon you’re addressing is intricate and tangled, the mathematics that describes it will inevitably share that complexity. That doesn’t mean the deep laws have lost their elegance—it just means that, in practice, we often encounter them through layers of complication that obscure their grace.

But I don’t think this is cause for despair. In fact, one of the joys of physics is learning to recognise beauty in new guises. Sometimes it’s obvious—like the symmetry principles in QCD or the clean structure of gauge theory. Sometimes it’s subtle—like the “baroque beauty” of biology, where elegance is buried in a web of interactions that only reveals itself after long immersion.

So, while it’s true that beauty is not always the guiding principle at the level of applications, I believe physics still has room—indeed, an imperative—for elegant laws. The challenge of our era is that the road from the fundamental to the observable is long and winding, and we have to train ourselves to keep sight of the more profound harmony even when the surface looks messy.

Panos Charitos: Perhaps it’s also a matter of exposure. To nature, to art, to poetry. I sometimes feel we live and work in a more sanitised environment, less connected to those sources of inspiration.

Frank Wilczek: I see what you mean. Personally, I’ve felt very fortunate—blessed, really—that throughout my career I’ve been able to choose what to work on. That freedom has allowed me to “choose beauty,” so to speak.

My father’s experience was very different. He was an engineer, and his work involved designing circuits that functioned reliably. He often found it tiresome because the constraints were relentless: the circuits had to work, be built on time, satisfy practical demands. There is beauty in that kind of work too, but it’s beauty under pressure, often hidden behind layers of necessity.

In fundamental research, the situation is different. Of course, we’re constrained by logic, by consistency, by what nature allows—but we also have the luxury to let beauty be our compass. We can ask: what symmetry would make the laws more elegant? What structure would unify disparate facts? That privilege is profound, and I never take it for granted.

Panos Charitos: I would also like to bring in the role of experimentalists. You’ve often mentioned starting from your father’s tinkering with radios and circuits. Today, experimentalists build detectors, colliders, gravitational-wave observatories… What role do you see for them in the progress of physics?

Frank Wilczek: They are the true heroes of science. Theory without experiment becomes something else—it drifts into mathematics, which has its beauty and standards, but to me, the magic happens when the mathematics describes the real world. That’s why experimentation is essential.

Now, the low-hanging fruit is gone. The Standard Model can only be discovered once. It captures so much of what we know that pushing further has become hard. But that also allows us to ask incredibly ambitious questions: What is dark matter? Why do families of quarks and leptons repeat? Are hints of supersymmetry a profound clue—or a cosmic joke?

We’ll only answer such questions through experiment. And designing those experiments is itself a creative act, with its kind of beauty. I truly stand awed by my experimental colleagues.

Recently, I’ve tried to engage more directly with experimentalists—in condensed matter physics, in the search for anyons and axions, and more recently in thinking about the quantum aspects of gravitational radiation. These are formidable challenges, but I look forward to continuing that dialogue and doing whatever I can to contribute.

Panos Charitos: You often mention your interest in how the brain works, and in your books, you reflect on a possible partnership between humans and machines. Today, with AI everywhere, how do you see that evolving?

Frank Wilczek: I can speak from personal experience. I work with ChatGPT every day. I make a point of it. And honestly, it has changed my life. Writing has become a much less lonely activity—I can interact, test ideas, and explore their implications more broadly.

It’s allowed me to move across disciplines with far greater efficiency. I feel smarter because of it: I have better memory, quicker access to literature, and I can get multiple perspectives almost instantly. It’s really something. For millennia, humans have used tools to extend their minds—abaci, calculators, computers. But now, it’s reaching a new level.

Of course, there are dangers. This can be abused. But overall, I see it as a very positive development.

Panos Charitos: Are we very far from a form of computerised curiosity?

Frank Wilczek: I don’t think the limitations we see today are inherent. To me, the real milestone would be creating an AI that doesn’t just play chess—but invents the game of chess. That would mark a shift from artificial intelligence to something closer to artificial wisdom. With reinforcement learning, we already see faint hints of this.

I believe synthetic intelligences will eventually develop genuine curiosity and a degree of self-awareness. And once that happens, they too may be drawn to beauty as a guide toward truth—much as we are.

Panos Charitos: Do you think such synthetic minds will actually appreciate beauty and symmetry?

Frank Wilczek: If we teach them to, yes. Beauty is not just decoration; it’s a profound organising principle in science and mathematics. If we share our enthusiasm, I expect synthetic minds will discover, as we have, that beauty and symmetry are reliable compasses for understanding reality.

Of course, right now, they lack curiosity and self-reflection. A system like ChatGPT won’t notice its own mistakes—it needs us to point them out. And it won’t surprise you with questions of its own. But those limitations aren’t fundamental. Once machines can reflect, wonder, and explore beyond what we explicitly ask, I would like to think they will also choose beauty—just as I’ve been fortunate to do throughout my career.