Interview with Ugo Amaldi: Reflections on CERN's 70-Year Legacy and European Collaboration

Portrait photo of Ugo Amaldi. Credits: Marina Cavazza, Copyright@CERN

In the landscape of 20th-century European science, few figures loom as large as Edoardo Amaldi, a pioneering physicist who played a crucial role in establishing some of Europe's most transformative scientific institutions. His son, Ugo Amaldi, carries forward this remarkable legacy of scientific collaboration and innovation. As CERN celebrates its 70th anniversary, Ugo offers a unique, intimate perspective on the birth of Big Science in post-war Europe—a period when visionary scientists like his father worked to rebuild scientific infrastructure and forge international cooperation.

As a member of a remarkable scientific family, Ugo Amaldi witnessed and participated in some of the most transformative moments in 20th-century physics. From the post-war reconstruction of European science to groundbreaking experiments at CERN, his career spans a critical period of scientific development. Beyond his research, he continued his parents' legacy of scientific communication, co-authoring textbooks that have educated generations of Italian students.

In this interview, Amaldi offers a deeply personal and historically rich perspective on the evolution of European physics, the birth of international scientific collaboration, and the human stories behind major scientific discoveries. His narrative is not just about physics, but about vision, perseverance, and the profound human connections that drive scientific progress.

Panos Charitos: Should we start with your father's involvement in the founding of CERN?

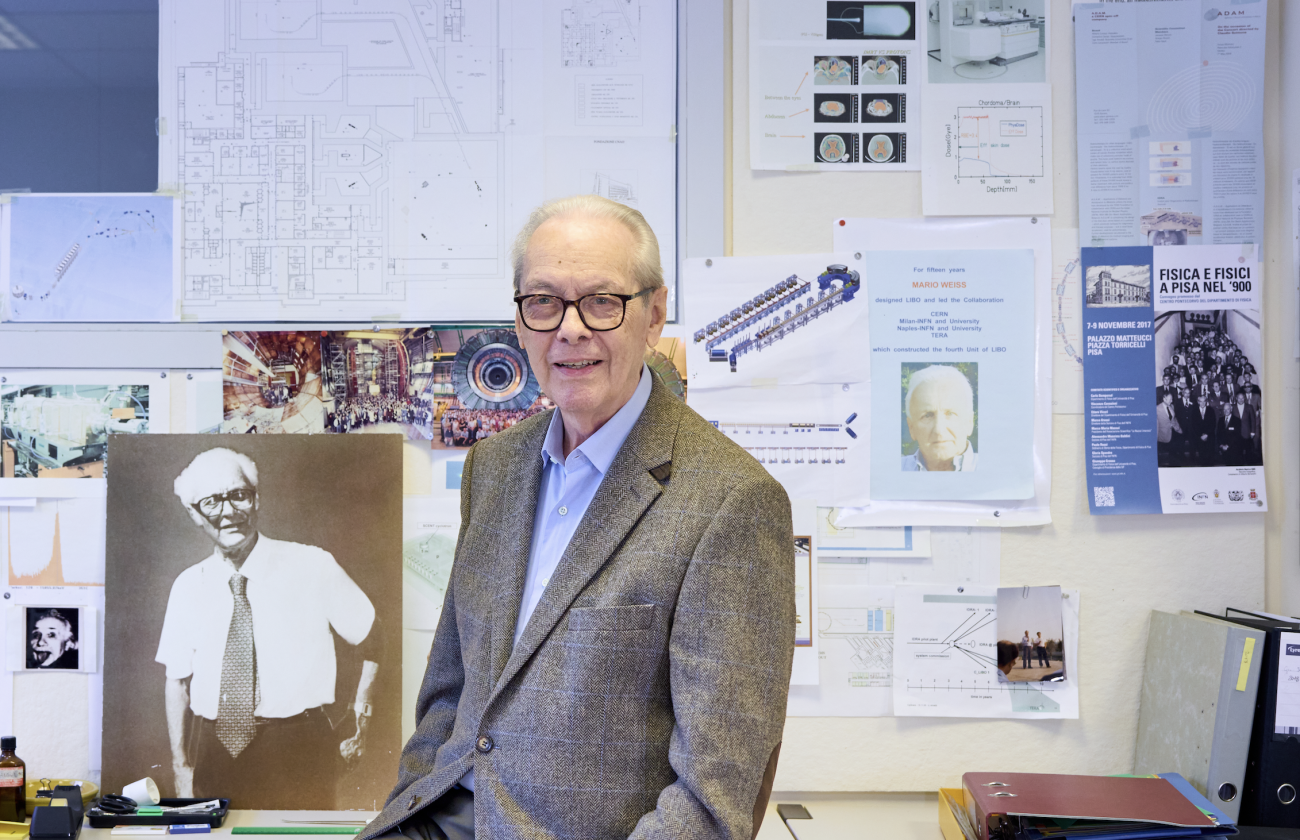

Ugo Amaldi: Well, I was born in 1934, so in 1952, when my father became Secretary General of CERN, I was just entering university. But perhaps I should start a bit earlier because I have some possibly interesting context to share.

I began hearing my father talk about a new European laboratory while I was still in high school in Rome. He often discussed at lunch this "European Laboratory" with my mother, who was also a scientist. She had studied physics and completed a 1931 thesis in astronomy, but women were not allowed at the institute of Via Panisperna, where Fermi and his collaborators were working. Instead, she became a well-known writer of science books for laymen and, in particular, young people. For the first one – published in 1936 with the title ‘Alchemy of our time” – she collaborated with Laura Fermi—Enrico Fermi's wife. It was published in 1936 when I was three, and it was republished this year by Castelvecchi Editor, 30 years after my mother's passing.

Our lunch table was always alive with discussions about science, physics, and the vision of this new laboratory. Later, I learned that in 1948-1949, my father was deeply engaged in these conversations with two of his colleagues: Gilberto Bernardini, a well-known cosmic ray expert, and Bruno Ferretti, a professor of theoretical physics at Rome University. Those table discussions remain vivid in my memory.

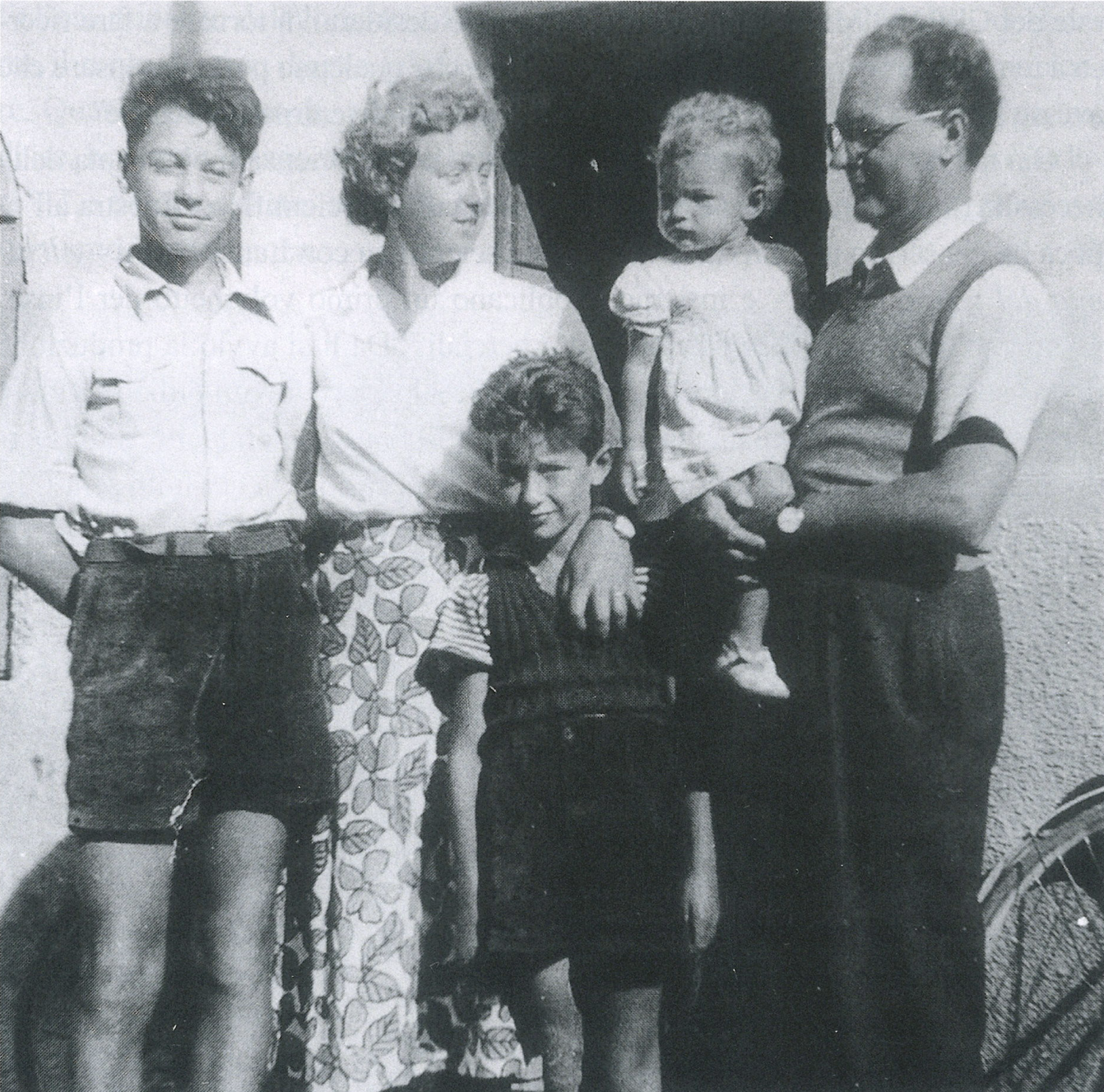

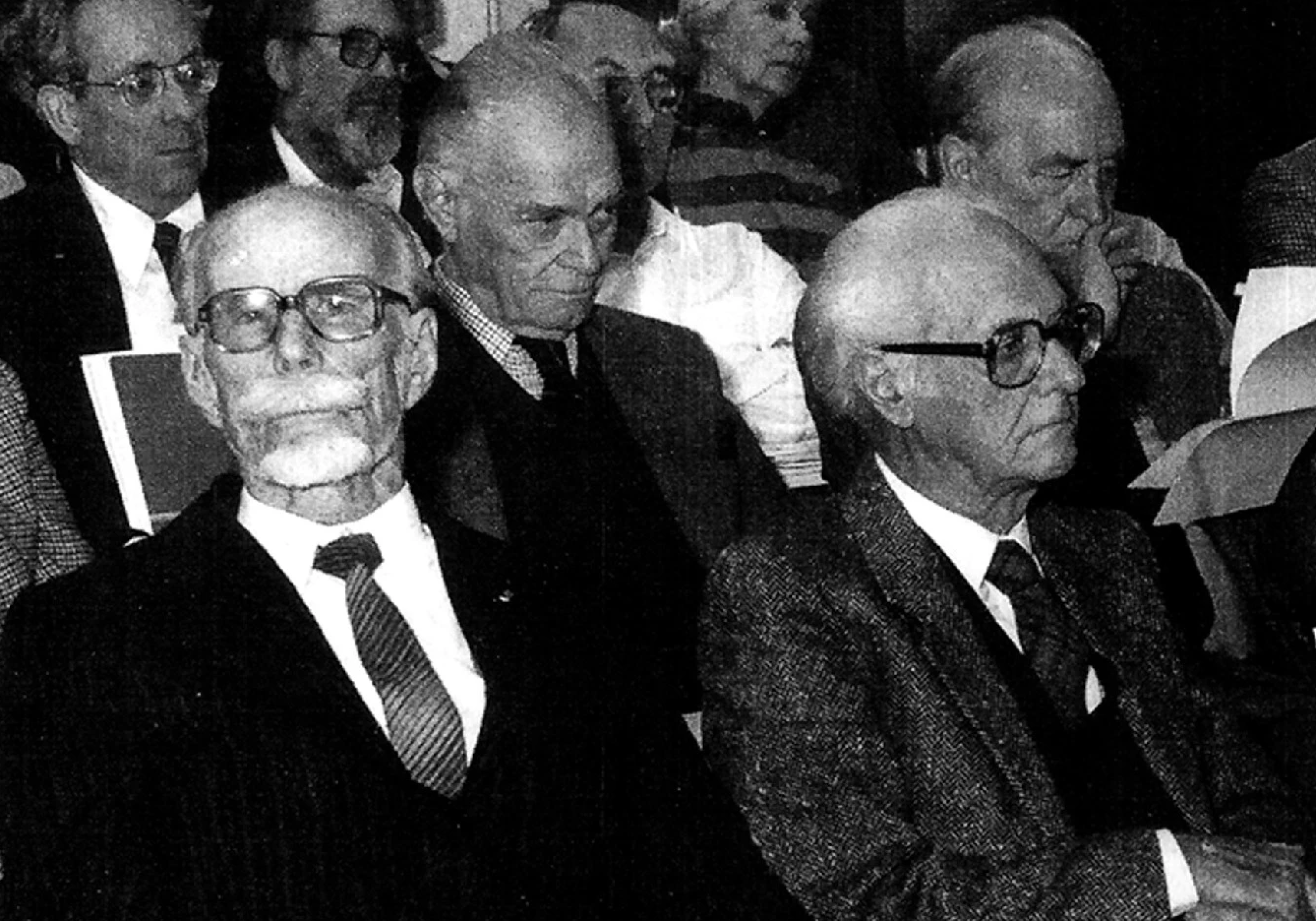

Edoardo Amaldi, Gilberto Bernardini and Ettore Pancini in 1947 at the Testa Grigia laboratory located in Cervinia (Dolomites) near the Italian-Swiss border.

So, the idea of a European laboratory was already being discussed before the UNESCO meeting in 1950?

Yes, indeed. As one can read in the volumes on the history of CERN, as well as in other books, many discussions were happening both in Europe and the USΑ, so many threads must be followed to get the full picture. On my side, I know quite directly (also because some of them were invited for lunch in our Rome apartment) that several eminent European physicists, including my father, Pierre Auger, Lew Kowarski, and Francis Perrin, recognized that Europe could only be competitive in nuclear physics through collaborative efforts. All the actors wanted to create a research centre that would stop the post-war exodus of physics talent to North America and help rebuild European science.

I now know that my father's involvement began in 1946 when he travelled to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to present a conference paper. There, he met Nobel Prize winner John Cockcroft, and their conversations planted in his mind the first seeds for a European laboratory.

Parallel to scientific discussions, there was an important political initiative led by Swiss philosopher and writer Denis de Rougemont. After spending the war years at Princeton University, he returned to Europe with a vision of fostering unity and peace. He established the Institute of European Culture in Lausanne, Switzerland, where politicians from France, Britain, and Germany would meet. In December 1949, during the European Cultural Conference in Lausanne, French Nobel Prize winner Louis de Broglie sent a letter advocating for a European Laboratory where scientists from across the continent could work together peacefully.

Two of CERN’s founding fathers: Pierre Auger and Edoardo Amaldi pictured in 1953 (Credits: CERN)

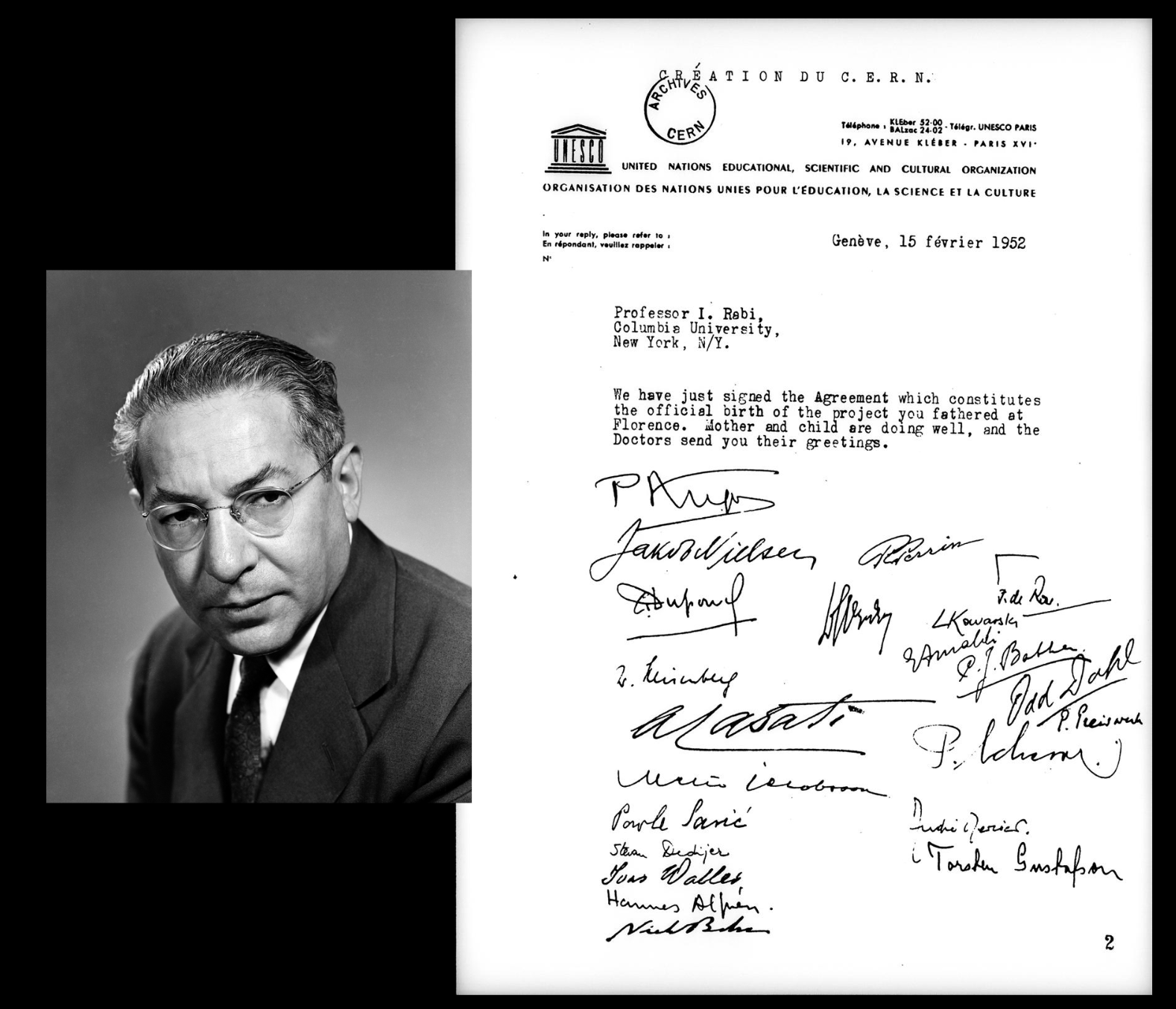

How did Isidor Isidor Rabi's involvement come into play?

In 1950, my father was corresponding with Gilberto Bernardini, a friend and professor in Rome University who was spending a year at Columbia University. It is certain that Bernardini mentioned the idea of a European laboratory to Isidor Rabi, who, at the same time, was in contact with other prominent figures in this decentralized and multi-centered initiative. Together with Norman Ramsay, Rabi had previously succeeded, in 1947, in persuading nine northeastern U.S. universities to collaborate under the banner of Associated Universities, Inc., which led to the establishment of Brookhaven National Laboratory.

What is not generally known is that before Rabi gave his famous speech at the 5th Assembly of UNESCO in Florence (June 1950), he came to Rome and met with my father. They discussed how to bring this idea to fruition. Rabi even gave - on June 5, 1950 - a seminar in Rome on the scattering of electrons on neutrons and invited my parents for dinner. Following a suggestion of mine to look for a seminar that certainly my father would have asked Rabi, a science historian, Adele La Rana - who had been working with me on my high-school books - looked into the subject and found a publication from the National Research Council (CNR) listing this seminar among the seminars given that year in the Rome Physics Institute. Moreover, I clearly remember the following episode: a morning of that period, my mother told me, “Last night, in a Trastevere ‘osteria’, we ate a steak as we never had since before the war”. A few days later, Rabi's resolution at the UNESCO meeting, calling for regional research facilities, was a crucial step in launching concretely the project.

Why did Rabi later deny that he met with your father in Rome?

It is thus sure that Rabi met with my father before his UNESCO speech, even if Rabi always denied it. My father could never understand why Rabi denied it. Probably he was very proud of his initiative and did not want to share the merit with somebody else. On the other side, he was a wise man, and it is very natural - as remarked by science historian John Krige - that he wanted, before speaking in Florence, to be sure that somebody competent in the field and well-known by the European physics community, would take up his proposal and carry it forward.

What was Rabi's proposal at the UNESCO meeting?

Rabi presented a resolution at the UNESCO conference, calling on the organization to help develop regional research facilities "to increase and make more fruitful the international collaboration of scientists." While the resolution didn't mention nuclear physics explicitly, it was clear in the Florence discussions that the purpose was to build a large particle accelerator in Europe.

It's important to understand the context of the time. Rabi's declaration crystallized the growing momentum for a European laboratory, but it built upon earlier efforts by scientists and politicians. I think that without the considerable preparatory work done by many, including my father, Rabi's initiative would not have brought fruit.

What motivated Rabi to make this proposal?

One of the key motivations behind creating CERN was the need to build large-scale accelerators in Europe. Rabi considered CERN also a peaceful compensation for the fact that physicists had built the nuclear bomb. At CERN's 30th anniversary celebration in 1984, he said:

"CERN was founded less than 10 years after the bomb was made. I feel that the existence of the bomb and its success had a large part in making CERN possible. I expected that Europe, which was the cradle of science, once brought back into the path, would achieve some very great things. I hope that the scientists at CERN will remember that they have other duties than exploring further into particle physics. They represent the combination of centuries and centuries of investigation study, and scholarship to show the power of the human spirit. So, I appeal to them not to consider themselves as technicians but as guardians of this flame of European unity so that Europe can help preserve the peace of the world.”

My father strongly believed in the importance of accelerators to advance the new field that, at the time, was at the crossroads between ‘nuclear physics’ and ‘cosmic ray physics’. Before the war, in 1936, he had travelled to Berkeley to learn about cyclotrons from Ernest Lawrence. He even attempted to build a cyclotron in Italy in 1942, profiting from the World’s Fair that had to be held in Rome. Moreover, he was deeply affected by the exodus of talented Italian physicists after the war, including Bruno Rossi, Gian Carlo Wick, and Giuseppe Cocconi. He saw CERN and its accelerators as a way to bring these scientists back and rebuild European physics.

This photograph from CERN's 30th anniversary in September 1984 captures a significant moment in the history of CERN. Pierre Auger, a key figure in CERN's early days, is seen alongside Edoardo Amaldi. Seen between them is Denis de Rougemont (1906-1985) founder of the European Cultural Centre where first discussions for a European laboratory were held. On the right is Jean Mussard, Auger's assistant at UNESCO.

How did your father and his colleagues proceed after the UNESCO resolution?

Following the UNESCO meeting, my father, and Pierre Auger, at that time Director of exact and natural sciences at UNESCO, took on the task of advancing the project. At a meeting of the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP) in September 1950, my father – who was one of the vice presidents – urged the Executive Committee to consider how best to implement the Florence resolution. A few weeks later, Auger spoke at the Oxford Nuclear Physics Conference.

On September 15, 1950, my father wrote to Isidor Rabi: “At the meeting of the Executive of the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics held in Cambridge Massachusetts the 7th and th 8th of September, there was some discussion on your proposal for the construction of an European nuclear physics laboratory. …The executive of IUPAP decided to ask for two reports on this subject: the first one from you and the second one from me. Your report is expected to contain all the details you have in mind about the construction, financial support and operation of such an international laboratory. My report, which is expected to be independent of yours, will contain a resumé of the opinion of European physicists, which I’ll contact by letter. … I beg you to write to me as soon as possible what is, or are, the various possibilities that you consider more feasible. ”

Auger then convened a pivotal meeting of physicists and science administrators in Geneva in December 1950, where my father and Gustavo Colonnetti, the president of the Italian Research Council, represented Italy.

In May 1951, Auger and my father organized a meeting of experts at UNESCO headquarters in Paris, where a compelling justification for a collaborative European project was drafted. The cost of such an endeavour was beyond the means of any single nation. This led to an intergovernmental conference under the auspices of UNESCO in December 1951, where the foundations for CERN were laid.

Funding, totalling 10,000 USD, for the initial meetings of the Board of Experts came from Italy, France and Belgium, with Italy being the first to contribute. This was thanks to the financial support of men like Colonnetti, an influential person who believed in the importance of scientific research.

Were there any significant challenges during this period?

Νοt everyone readily accepted the idea of a European laboratory. Eminent physicists like Niels Bohr, James Chadwick, and Hendrik Kramers questioned the practicality of starting a new laboratory from scratch. They were concerned about the feasibility and allocation of resources and preferred the coordination of many national laboratories and institutions.

Through skilful negotiation and compromise, my father and Auger incorporated some concerns raised by the sceptics into a modified version of the project, ensuring broader support. In February 1952, the first agreement setting a provisional council for CERN was written and signed, and my father was nominated Secretary General of the provisional CERN. He worked tirelessly, travelling through Europe to unite the member states and start the laboratory's construction.

In particular, the UK was reluctant to participate fully. They had their own advanced facilities, like the 400 MeV cyclotron at the University of Liverpool. In December 1952 my father visited Sir John Cockcroft, a Nobel prize winner at the time Director of Harwell, to discuss this. There's an interesting episode where my father, with Cockcroft, met Frederik Lindeman, Baron Cherwell, who was a long-time scientific advisor to Winston Churchill. Cherwell dismissed CERN as another "European paper mill." My father, usually composed, lost his temper and passionately defended the project. During the following visit to Harwell, Cockcroft reassured him that his reaction was appropriate. Indeed, from that point on, the UK contributed to CERN, albeit initially as a series of donations rather than as the result of a formal commitment. It may be interesting to add that, during the same visit to London and Harwell, my father met the young John Adams and was so impressed that immediately offered him a position at CERN.

Which were the steps following the ratification of CERN's convention?

Robert Valeur, who served as Chairman of the Council during the whole of the interim period, and Sir Ben Lockspeiser, Chairman of the Interim Finance Committee, used the full extent of their authority to stir up early initiatives and create an atmosphere of confidence which attracted scientists from all over Europe. As Kowarski notes, there was a sense of "moral commitment" to leave their secure positions at home and embark on this new scientific endeavour in Geneva.

The first meeting of the provisional CERN Council on 15 February 1952, with key people including Sir Ben Lockspeiser, Edoardo Amaldi, Felix Bloch, Lew Kowarski, Cornelis Bakker and Niels Bohr (at the back).

During the interim period from May 1952 to September 1954, the Council convened three sessions in Geneva: in October 1953, January 1954, and April 1954, with a final formal winding-up session in October 1954. The primary focus of these sessions was financial management. The organization began with an initial endowment of approximately 1 million Swiss Francs, which – as I said – included a contribution from the United Kingdom known as the "observers' gift".

As the organization's activities expanded, additional financial contributions became necessary. At each subsequent session, the Council increased its funding, ensuring that the interim stage's financial needs were fully met. By the end of this period, the total expenditure had reached around 3.7 million Swiss Francs. When the permanent Organization was established, an initial sum of 4.1 million Swiss Francs was made available.

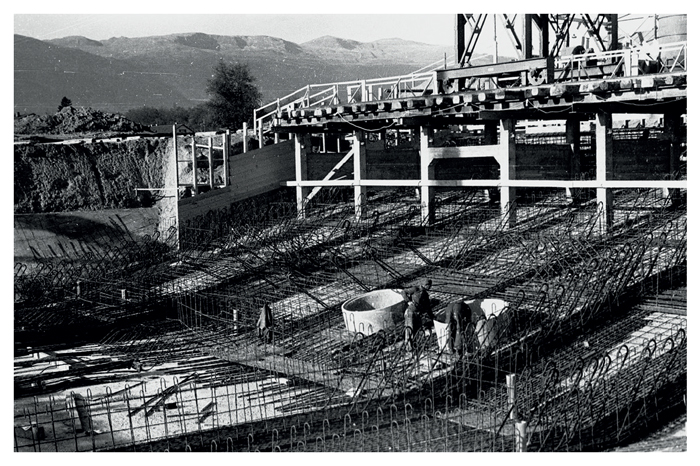

In 1954, my father was worried that if the parliaments didn't approve the convention before winter, construction would be delayed because of the wintertime. He took a bold step and, with the approval of the Council President, authorized the start of construction on the main site before the convention was fully ratified. This led to Lockspeiser jokingly remarking later that Council "has now to keep Amaldi out of jail."

The provisional Council, set up in 1952, was dissolved when the European Organization for Nuclear Research officially came into being in 1954, though the acronym CERN (Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire) was retained.

By the conclusion of the interim period, CERN had grown significantly. A critical moment occurred on September 29, 1954, when a specific point in the ratification procedure was reached, rendering all assets temporarily ownerless. During this eight-day period, my father, serving as Secretary General, bore the unique responsibility of sole ownership on behalf of the newly forming permanent Organization. The interim phase concluded with the first meeting of the permanent Council, marking the end of CERN's formative years.

By November 1954, the foundations of the machine hall and experimental halls for the Synchrocylcotron, CERN’s first accelerator, were taking the shape of a rigid “raft”.

Did your father ever consider becoming CERN's Director-General?

People asked him to become Director-General, but he declined for two reasons. First, he wanted to return to his students and his cosmic ray research in Rome. Second, he didn't want people to think he had done all this to secure a prominent position. He believed in the project for its own sake.

When the convention was finally ratified in 1954, the Council offered the position of Director-General to Felix Bloch, a Swiss American physicist and Nobel Prize winner for his work on nuclear magnetic resonance. Bloch accepted but insisted that my father serve as his deputy. My father, dedicated to CERN's success, agreed to this despite his desire to return to Rome full-time.

How did that arrangement work out?

My father agreed, even though he preferred to return to academia because he wanted CERN to succeed. Bloch, however, wasn't at that time rooted in Europe. He insisted on bringing all his instruments from Stanford so he could continue his research at CERN. He found it difficult to adapt to the demands of leading CERN and soon resigned. The Council then elected Cornelis Jan Bakker, a Dutch physicist who had led the synchrocyclotron group, as the new Director-General. From the beginning, he was the person my father thought would have been the ideal Director for the initial phase of CERN. Tragically, Bakker died in a plane crash a year and a half later. I well remember how hard my father was hit by this loss.

You mentioned earlier that your father had tried to build accelerators in Italy before CERN was established. Could you please tell us more about that?

In 1936 Fermi attempted to build a cyclotron in Italy and sent my father to Berkeley to learn from Ernest Lawrence. After Fermi left, Gilberto Bernardini and my father even planned to use the Universal Exhibition of 1942 in Rome, intended as a showcase of Italian Fascism successes, to secure funding for a cyclotron. The idea was to display it at the exhibition and use it as a research instrument afterwards.

Unfortunately, the war disrupted these plans. After the war, resources were scarce, but my father continued to advocate for building accelerators. As many others, he recognized that cosmic ray studies were becoming insufficient for advancing the field and that the accelerators, being built at the time in the USA but also in the UK, were necessary to explore higher energies under controlled conditions.

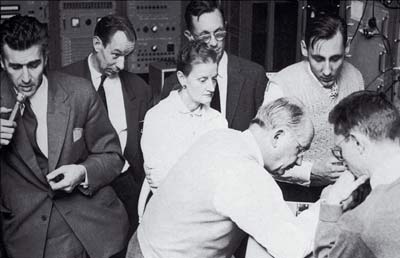

How did the development of accelerators at CERN progress?

The decision to adopt the strong focusing principle for the Proton Synchrotron (PS) was a pivotal moment. In August 1952, Otto Dahl – leader of the Proton Synchrotron study group - Frank Goward and Rolf Widerøe visited Brookhaven just as Ernest Courant, Stanley Livingston, and Hartland Snyder were developing this new principle. They were so excited by this development that they returned to CERN, determined to incorporate it into the PS design. In 1953 Mervyn Hine, a long-time friend of John Adam with whom he had moved to CERN, studied potential issues with misalignment in strong focusing magnets, which led to further refinements in the design. Ultimately, the PS became operational before the comparable accelerator at Brookhaven, marking a significant achievement for European science.

Members of the PS commissioning team cluster around an oscilloscope (24 November 1959). Left to right: John Adams, Hans Geibel, Hildred Blewett, Lloyd Smith, Chris Schmelzer, Wolfgang Schnell and Pierre Germain. Read the story behind the photo in a CERN Courier article by Hildred Blewett. Image credit: B Sagnell.

It's important to recognize the crucial contributions of engineers, who often don't receive the same level of recognition as physicists. They are the ones who made possible the work of experimental physicists and theorists. About this, ‘Viki’ Weisskopf, Director General of CERN from 1961 to 1965, wrote: “There are three kinds of physicists, namely the machine builders, the experimental physicists, and the theoretical physicists. The machine builders are the most important ones because if they were not there, we would not get into this small-scale region of space. If we compare this with the discovery of America, the machine builders correspond to captains and shipbuilders who really developed the techniques at that time. The experimentalists were those fellows on the ships who sailed to the other side of the world and then landed on the new islands and wrote down what they saw. The theoretical physicists are those who stayed behind in Madrid and told Columbus that he was going to land in India.” Inspired by this, I even published in 2015 with Springer a book titled “Particle Accelerators: from Big Bang physics to hadron therapy” in which I concentrate on the lives and contributions of particle accelerator physicists and engineers following my motto: “Physics is beautiful and useful”. Now, after ten years, the book can be freely downloaded from the Springer site.

One such unsung hero is Wolfgang Schnell. He played a vital role in getting the PS operational. Although he was a physicist by training, he had a deep understanding of accelerator technology. I remember seeing him at CERN in those early days. He may not have had a long list of scientific publications, but his practical knowledge was invaluable to the success of the PS. Many years later, Wolfgang Schell invented the very high-frequency linear electron-positron colliders, which has been developed at CERN under the acronym of CLIC, which stands for Compact Linear Collider.

While there was a spirit of scientific collaboration, there was also healthy competition. The goal was to advance knowledge, but achieving milestones before others was a matter of pride and a demonstration of Europe's renewed scientific capabilities

Interviewer: I also wanted to touch upon your father's contributions to nuclear disarmament and the birth of the European Space Agency (ESA). I think these are important aspects of his legacy.

Ugo Amaldi: Yes, indeed. In addition to his work with CERN, my father made significant contributions to nuclear disarmament and in 1958 was instrumental, together with Pierre Auger, in the founding of ESA. He wrote the first draft of the paper Space Research in Europe, aiming to stimulate discussions on the formation of a European organization for space research. A French version of this letter “Créons une organization européenne pour la recherce spatiale” was published in the French journal L’Expansion de la Recherche Scientifique in December 1959 [see also here] together with supportive coments from scientists from several countries. In Amaldi’s original vision, not only the development of the satellites – the “Eurolunas” – but also that of their launchers would be the responsibility of the organization, which would need experts in the technology and engineering of rockets as well as space scientists. Moreover, in collaboration with Guido Pizzella, my father also searched for gravitational waves with large resonant bars from 1971 until his death in 1989. One of these superconducting bars was installed at CERN to utilize the expertise on large liquid helium instruments available there.

Because of his dedication to these two themes, there are two series of conferences named after him. The first is the Edoardo Amaldi Conference on International Cooperation for Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy, focusing on disarmament and arms control. Luciano Maiani is currently the chairman of this series. The second is the Edoardo Amaldi Conference on Gravitational Waves, the most important conference in the field of gravitational wave research, which is held every two years. These conferences are significant legacies of my father's work beyond CERN.

Cover of the Amaldi folder signed by the cosmonauts aboard the International Space Station. Read more in this article (CERN Courier, May 2012).

That's remarkable. Your father had a profound impact on various fields and the development of Big Science organizations in Europe, including ESA.

Yes, and if you visit ESA's website, you'll find that his crucial role in ESA foundation – again with Pierre Auger – was recognized when, in 2012, one of the Automated Transfer Vehicles (ATVs), the ATV-3, was named after him. These were spacecraft used to supply the International Space Station. The first was named after Jules Verne, the second after Johannes Kepler, and the third, ATV-3, after Edoardo Amaldi. It was a significant recognition of his contributions.

In addition to its primary cargo, the ATV carried a reproduction of a letter written in 1958 by Edoardo Amaldi to his friend Crocco, who was Professor of Jet Propulsion in Princeton:

“After our discussion in Salvini’s home in Rocca di Papa at the end of July, I thought over the possibility of developing an appropriate activity in Europe in the field of rockets and satellites. It is now very much evident that this problem is not at the level of the single states like Italy, but mainly at the continental level. Therefore, if such an endeavour is to be pursued, it must be done on a European scale, as already done for the building of the large accelerators for which CERN was created. The launch of one or more Euroluna, performed by a dedicated European organization, would definitely be of the highest importance, both moral and practical, for all the nations of the continent…. During the Conference of Geneva, held in the first half of September, I had the opportunity to discuss with Rabi, who reacted very positively and stated that, if this would be developed in the future, he would have done everything possible for obtaining the support of the United States. …I think it is absolutely imperative for the future organization to be neither military nor linked to any military organization. It must be a purely scientific organization open, like CERN, to all forms of cooperation and outside the participating countries.”

Poster distributed by ESA on the occassion of the launch of ATV3. Watch Ugo Amaldi's interview on ESA's dedicated website.

This document reflects my father's vision of a peaceful and non-military European science. Ten copies of this five-page letter were flown onboard the ATV3, signed by the astronauts, and brought back to Earth by a Soyuz launcher. One copy was donated by ESA to CERN.

How is it possible for one person to contribute so profoundly to science and international collaboration?

Looking back, it might seem incredible. His success was due to his clear vision and his ability to accept defeats gracefully. He was persistent and never gave up, even when faced with opposition. For example, after initial discussions about CERN, as I said, there was significant opposition from well-respected physicists. Despite this, my father and Pierre Auger continued to advocate for the European laboratory. In my view, this was a sign of how creative and persuasive they could be.

If I may say, my father's ability to accept defeats and keep pushing forward was key to his success. He was an exceptional person with a clear vision and unwavering dedication. I hope that by sharing these stories, others might be inspired to pursue their goals with the same persistence and passion.

Could we argue that he was not only a visionary but also a relentless advocate?

He travelled extensively, talked to countless people, and was always cheerful and energetic. He accepted setbacks but kept pushing forward. In this connection, I want to mention Eliane Bertrand (1917-2004), who later became Eliane de Mozelewska; she was his secretary in Rome and later became the Secretary of the CERN Council for about 20 years, serving under several Director-Generals. She left a memoir about those early days, highlighting how my father was always travelling, talking, and never stopping. It's a valuable piece of history that, I think, should be published.

Coming to your trajectory, how natural was it for your parents that you decided to study physics?

In 1952, I finished high school and told my parents I wanted to study physics at university. My father initially opposed this—not because he doubted my abilities, but because he felt it would be difficult for me to establish my identity in the same field where he was well-known. He even suggested that I should consider biology. For him “Biology is exploding”; indeed, next year, the structure of DNA was discovered by Crick and Watson. Despite his reservations, I enrolled in physics without initially telling him. When I did inform my parents, my father accepted it, and I think he was happy with my decision. For about 20 years, starting in 1971, on Sunday evenings, we would talk over the phone between Rome and Geneva when the cost per minute was lower, but only after describing what my two daughters and two sons had done during the past week.

And what do you recall from your first steps at CERN?

In September 1961, I arrived as a fellow at CERN and started to work in the group of Guisepe Fidecaro. Clelia and I were just married, and our first daughter was born seven months later in Chêne-Bougeries. After two years, I returned to work at the Physics Laboratory of the Italian National Health Institute, where I did nuclear and atomic physics experiments. When in 1971 we came back to Geneva, we already had our two daughters and two sons.

I joined the Experimental Physics Division as a research associate, working with Giorgio Matthiae at the Intersecting Storage Rings (ISR). Building on our previous experience from Rome, we developed the Roman pots technique by collaborating with a CERN group led by an extraordinary senior physicist: Giuseppe Cocconi. Together, we made a significant discovery about the rise in energy of the proton-proton cross-section. In the CERN-Rome collaboration, I was the only one analysing the data, so I can say that I lived exciting years. By 1973, I had a CERN indefinite contract, and I was presenting our findings at conferences and even was asked tio write an article in Scientific American about high-energy proton-proton interactions.

My scientific interests were expansive - in 1975, I explored diverse territories, from proposing a superconducting electron-positron linear collider to initiating a new line of research with Klaus Winter and Guido Barbiellini on neutrino physics with the CHARM collaboration.

Pushing scientific boundaries always excited me. When I proposed measuring the polarization of muons produced by neutrinos from the SPS, high-level physicists like Jack Steinberger deemed it impossible because the rate would be infinitesimal. However, I had carefully done my homework, and it was soon accepted that it was indeed possible to stop the muons produced by the neutrinos in the iron of the CDHS calorimeter, placed upstream in the SPS neutrino beam, in our CHARM detector. We could then make their spin precess in a low magnetic field to measure their polarization.

After the SPS inaugural ceremony (May 1977): Vanna Cocconi, Giuseppe Cocconi, Endre Lillethun, Ugo Amaldi. On the background, Arne Lundby.

The most creative aspect of this endeavour was the selection of the detector material. We needed a nucleus that wouldn't depolarize the muons, and we found that calcium carbonate was the best choice. Thus, over 400 tons of marble were transported from Michelangelo's quarries in Carrara to CERN. With 4mx4m thin slabs we constructed an enormous ‘muon polarimeter’ that was part scientific instrument, part artistic creation. When our measurements aligned with the Standard Model's predictions, the satisfaction was profound. These years at CERN were about more than research - they stimulated my imagination so that it happened to me to have on the same day the ideas of the muon polarization experiment and of the superconducting electron-positron collider.

In 1980, my dear friend Guido Barbiellini - an incredibly inventive physicist – asked me “Why, instead of joining others, do we not start asking friends and colleagues to form a collaboration to present a proposal for LEP?“ I hadn't considered this possibility, but I immediately agreed, saying, "Good idea." That spontaneous conversation became the seed of the DELPHI Collaboration, another exciting chapter in my scientific journey.

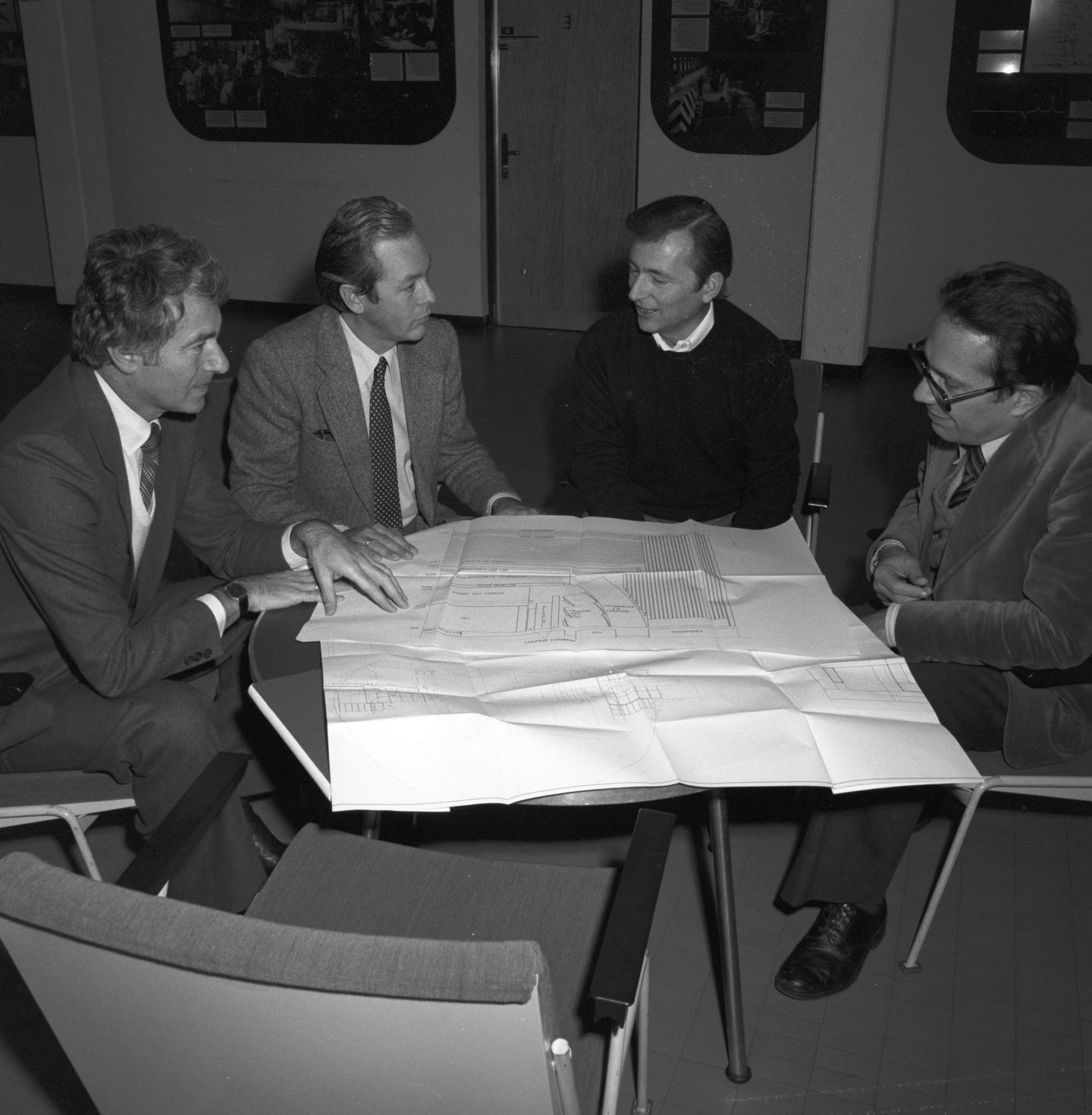

Discussion on the DELPHI, one of the four LEP experiments (December 1981): Around the table from the right: Guido Petrucci, Hans Jurgen Hilke, Ugo Amaldi, and Gregoire Kantardjian (Credits:CERN).

The DELPHI experiment was dismantled in 2001. The image shows all of the spokespersons of DELPHI. From right to left: Jean Eudes Augustin, Wilbur Venus, Tiziano Camporesi, Ugo Amaldi, Jan Timmermans and Daniel Treille. DELPHI "barrel" is still displayed at LHC Point 8 where the LHCb experiment is mounted.

Speaking of your own contributions, I understand that after your mother's illness, you took on the role of continuing the work on educational physics books.

Indeed. My mother, Ginestra, was an extraordinary science divulgator whose many books - addressed to the layman - were translated into multiple languages. Though she studied at the Enrico Fermi Institute in Rome, the limitations for women at that time prevented her from working there. Instead, she would write her books for the general public. In 1936, she wrote with Laura Capon (wife of Enrico Fermi), "Alchemy of our times", the first Italian popular science book covering from Democritus atom to the recent discoveries in nuclear physics. The book has been recently republished by Castelvecchi editions.

"Alchimia del nostro tempo" a book by Ginestra Amaldi and Laura Fermi. Ginestra Amaldi (1910-1994) was an extraordinary science communicator who overcame the barriers of her time by writing books that made complex physics accessible to everyone.

In parallel, my mother would collaborate with my father in the writing of textbooks for all types of high schools. She would write in the mornings when we were at school, and they would review them together in the evenings. Their collaborative process was fascinating but marked by a basic difference in the way in which physics should be explained, and this often caused long discussions.

My father maintained that, as an experienced horseman, “in order for horses to have a good gait and run fast, it is necessary for them to eat from a high crib”. For my mother, on the other hand, it was necessary to consider the pupils who are not racehorses; she said that “bread must be broken for the birds to eat it”. Those were the only times I saw our parents arguing - passionately but always respecting each other's opinion. Sometimes they could not agree, and my father would write or rewrite a particularly sensitive passage. As I began to deal with the physics books, I told my friends and collaborators of Zanichelli Editors about the two very different opinions: the ‘height of the crib’ and the ‘breaking of the bread of science’. The issue remained relevant, and even today, at Zanichelli, the subject of the ‘right’ height of the crib is evoked and debated.

I entered this activity because, when in 1971, my mother suffered an aneurysm at age 61, her writing capabilities were dramatically reduced. My father initially continued their work alone but, at the beginning of the 1980s, he asked me to help carry on this long-standing activity. When in 1989 he died I've been continuing their mission with Zanichelli Editors by writing textbooks that, for 35 years, have been used in more than one-third of all Italian high-school classes. One can estimate that more than two million pupils have studied physics in these textbooks. With the developments of an always larger set of coloured drawings, the website, the videos on experiments and the always-increasing number of exercises, the number of my collaborators has increased to about 15, and I am now the editor of a collective work.

It seems you played a significant role in fostering international collaboration.

Because of my father, I have always believed in bringing diverse scientists together. So, when we started DELPHI my goal was to include smaller groups and researchers from different backgrounds. We deliberately invited groups from Northern Europe and from the Soviet Union and brought in teams that hadn't traditionally worked on particle detectors - like Gerald Myatt's group from Great Britain and Jacques Lemonne's team from Belgium. These groups had been working with bubble chambers and had to learn detector technologies from scratch. The change happened in a few years, and the resulting detectors worked very well from the beginning. The importance of LEP experiments in this transition is, unfortunately, never underlined.

Since the beginning, I felt a responsibility to include groups that might have been overlooked by other collaborations like ALEPH or OPAL. Looking back, I'm proud of what we achieved. Many colleagues, including Daniel Treille and Chiara Mariotti, have spoken about the unique spirit of our DELPHI collaboration. We were not just doing science - we were building bridges between different scientific communities. In the exploitation phase, we considered the papers we were publishing not as a competition with the other three LEP experiments but as a second-order collaboration.

Looking ahead, what are your thoughts on the future of CERN and particle physics?

I firmly believe that pursuing higher collision energies is essential. While the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) has achieved remarkable successes, there's still much we haven't uncovered—especially regarding supersymmetry. Even though minimal supersymmetric models haven't been confirmed by observations, I remain convinced that supersymmetry might manifest in ways we haven't yet understood.

Exploring higher energies could reveal supersymmetric particles or other new phenomena. In this context, like most European physicists, I support the initiative of the Future Circular Collider (FCC). Starting with an electron-positron collider phase before transitioning to a hadron-hadron collider that would allow to methodically explore new frontiers at two very different energy levels.

However, if global conditions—such as geopolitical shifts —delay or complicate these plans, we should consider alternative strategies like developing the technologies for muon colliders.

International collaboration has been a recurring theme in your career. How do you view its importance in today's context?

International collaboration is more critical than ever in today’s world. Science has always been a bridge between cultures and nations, and CERN’s history is a testimony of what this brings to humanity. It transcends political differences and fosters mutual understanding. I hope CERN and the broader scientific community will find ways to maintain these vital connections. I've always believed that fostering a collaborative and inclusive environment is one of the main goals of us scientists. It's not just about achieving results but also about how we work together and support each other along the way.