EP R&D WP4 is developing innovative mechanical, thermal, and automation solutions to meet the unprecedented demands of next-generation collider detectors.

The next generation of detectors will face increasingly demanding challenges due to the large scale, precision, and extreme operating conditions of future colliders. Detectors for hadron colliders must cope with very high luminosity, leading to fast event rates, large particle fluxes, and extreme radiation. This requires radiation-resistant structures and active cooling at very low temperatures to protect the sensors. Lepton collider detectors, on the other hand, operate in lower-radiation environments and can function at room temperature. Their focus is on extremely precise tracking, high mechanical and thermal stability, minimal material budget, lightweight structures, and efficient gas cooling.

For both future collider types, detector mechanics must strike the right balance among unprecedented requirements for low mass, compactness, stability, radiation tolerance, and thermal performance.

In this context, WP4 – Mechanics of the EP R&D program, is seeking innovative solutions for the mechanical aspects of the full detector range, focusing particularly on the most demanding detectors. This includes the innermost vertex detector, the larger tracking system, the magnet, and the calorimeter, while also exploring more automated approaches for assembly and maintenance of the entire experiment.

From Vertex to Outer Calorimeter: R&D Challenges in Detector Mechanics and Installation

Vertex

The vertex detector, closest to the interaction point, faces the strictest requirements in spatial resolution, material budget, stability, and thermal management. Recent applications in ALICE demonstrate that Monolithic Active Pixel Sensors (MAPS) can be mounted on high-thermal-conductivity carbon substrates with embedded ultra-thin polyimide cooling pipes, achieving a material budget for the first layer as low as 0.35% X₀. Originally used for water cooling at room temperature in leakless (sub-atmospheric) mode, these pipes have been demonstrated through the EP R&D program to support high-pressure two-phase CO₂ cooling at detector operating temperatures as low as –35 °C. They can thus replace titanium or steel piping, providing a clear reduction in material budget, with a modest impact on cooling performance.

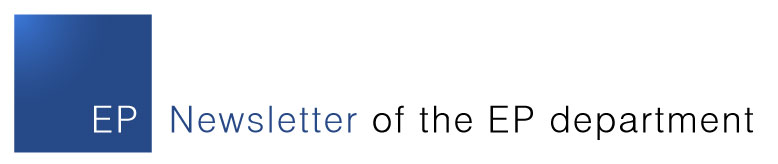

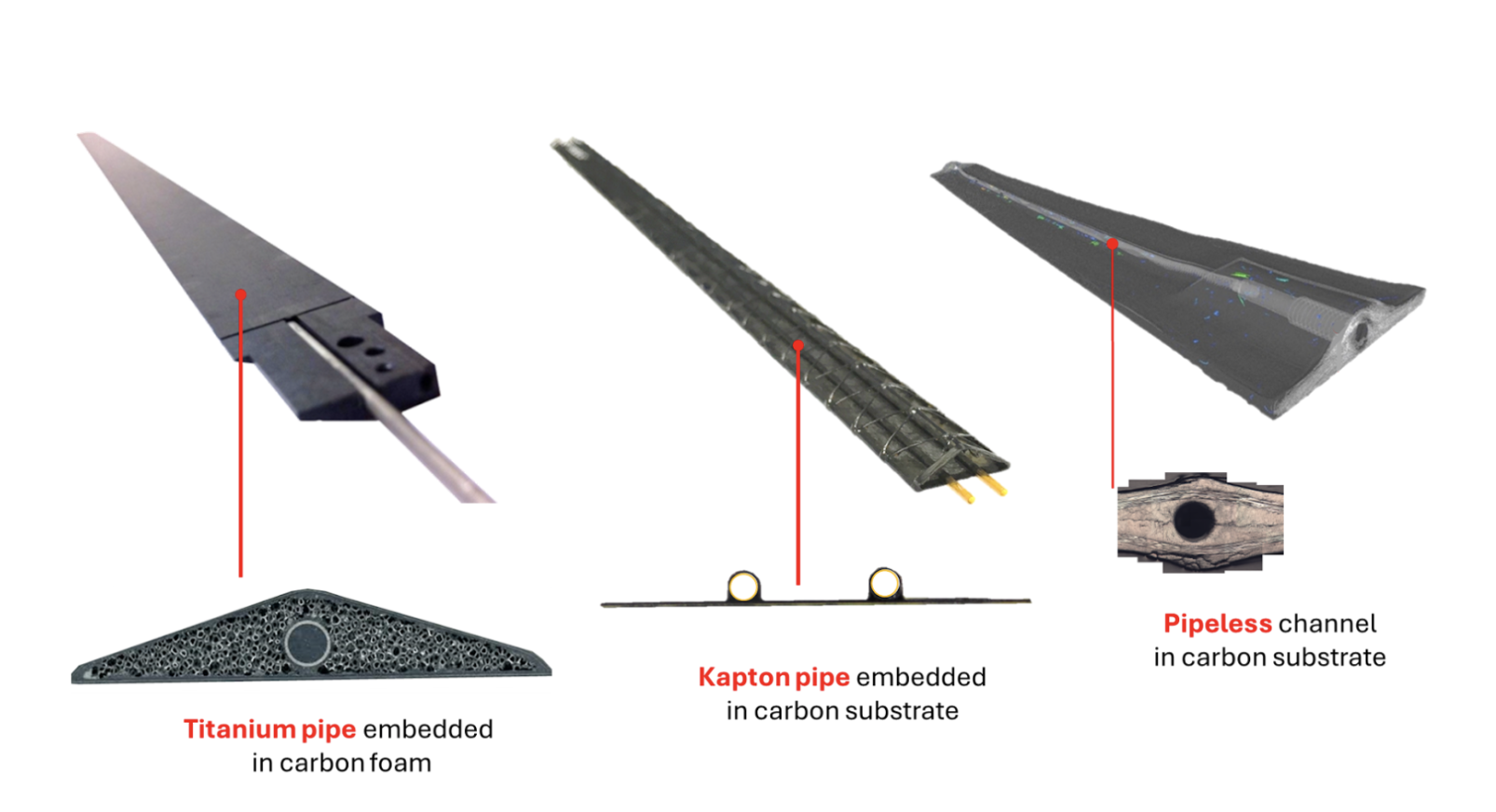

Ongoing R&D aims to further advance this concept by removing the Kapton pipes entirely and embedding a cooling network directly within the carbon substrate. Poly(lactic) acid (PLA) mandrels, 3D-printed in the desired channel geometry, are inserted during lamination of the substrate and later removed through a high-temperature cycle, leaving a fully integrated cooling network. This pipeless approach introduces new challenges, particularly regarding coolant–composite compatibility (e.g., two-phase CO₂) and potential chemical ageing, requiring dedicated experimental validation (Fig.1).

Figure 1 – R&D coldplate for tracking sensors: from titanium pipes to kapton pipes to pipeless channels for liquid and two-phase cooling solutions, aiming at minimum material budget.

While pursuing lighter substrate structures for high-radiation environments, where sensors must operate at very low temperatures, R&D is also exploring alternative refrigerants to go below –40 °C, beyond the limits of boiling CO₂. Supercritical or two-phase krypton (sKr) has emerged as a strong candidate, with work now focused on designing effective cooling cycles and systems. A krypton-based cooling system using an ejector, CO₂–krypton cascade, and passive expansion devices has been proposed for stable operation across supercritical and two-phase regimes. The system aims to handle temperature variations during a detector’s lifetime. Experimental tests on critical transients, such as startup and cooldown, were compared with numerical models. The next step is to finalize a test rig to validate the system’s performance in the ultra-low temperature range, comparing CO₂ and sKr cooling.

At the other extreme, in lepton colliders, in regions with moderate radiation levels and lower power consumption, tracker designs are moving toward eliminating active liquid cooling entirely, enabling passive air or gas cooling and significantly reducing material budget. Integrating power and data transmission directly within the monolithic sensor layer goes in the same direction, by stopping the services before entering the active area, with connectivity routed to the sensor edge.

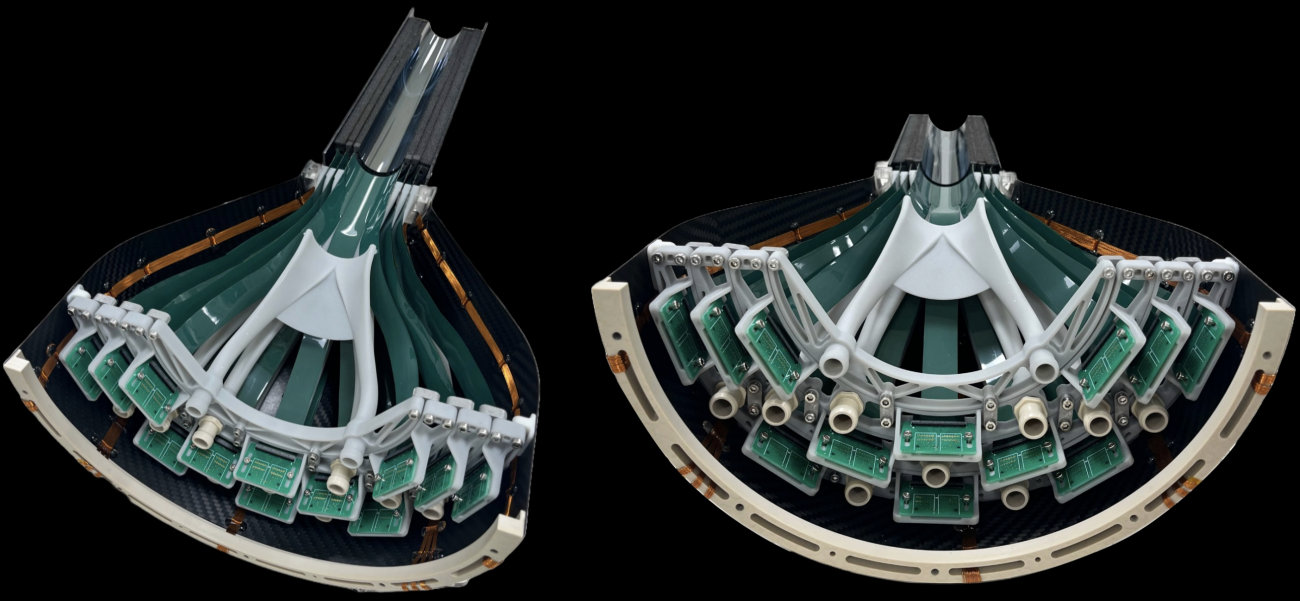

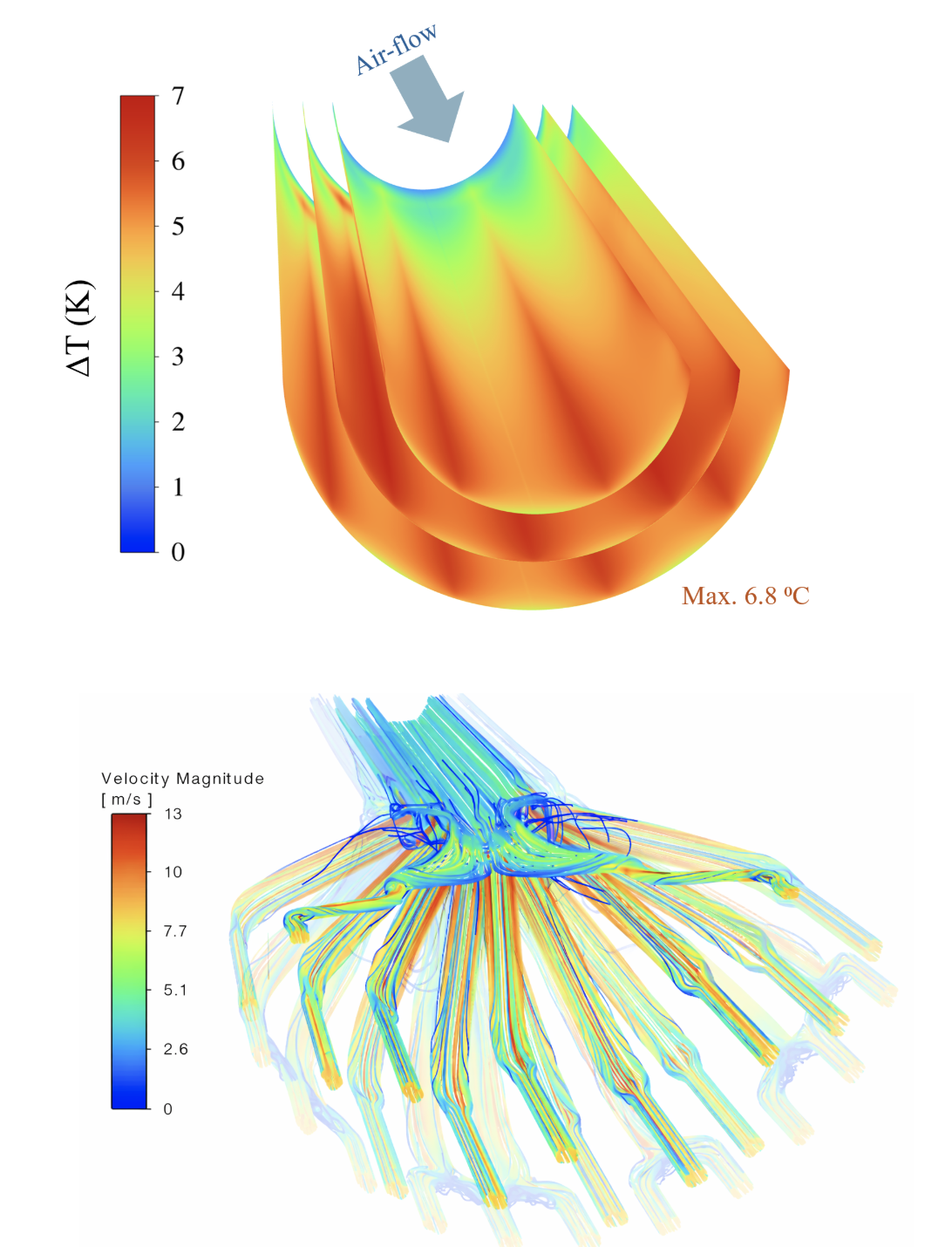

This approach, pursued in ALICE and within the EP R&D framework for the ITS3 vertex upgrade in LS3, uses wafer-scale MAPS produced in 65 nm CMOS with stitching technology, wrapped around the beam pipe to fully cover the cylindrical active area. The curved geometry gives the large sensors (~20 mm×260 mm) inherent rigidity, minimizing additional support structures. Carbon-foam rings and longerons at the periphery of the large sensors (~90 mm×260 mm), with a semicylindrical shape, function as both mechanical supports and thermal radiators. One of the carbon-foam rings is glued directly onto the sensor edge where most of the heat is dissipated through a very narrow surface. Heat is transferred by thermal conduction into the carbon foam, which significantly amplifies the surface area for heat exchange due to its cellular structure. The heat is then removed by air being flushed through the foam, much like a radiator. Materials such as Allcomp K9 and ERG Duocel carbon foams combine high thermal conductivity with very low mass. Controlled airflow blown into the radiators maintains sensors temperatures below 26 °C, while aeroelastic displacements remain of the order of ~1 μm ( 1.1 micron peak-to-peak; 0.5 micron RMS), achieving material budgets as low as 0.1% X₀ per layer (Fig.2).

Figure 2 – Three layers made of large scale bent sensors incorporating carbon foam radiators and support structures, including air cooling ducts (Top). Air cooling: flow velocity and sensors thermal maps (Bottom)

This fully integrated approach enables a new generation of ultra-light, mechanically stable, and thermally efficient vertex detectors, validated through a full engineering model in preparation for ALICE ITS3 construction.

Reducing material budget is challenging, but positioning the first detector layer close to the interaction point is equally crucial. The beam pipe, which maintains the vacuum for the particle beam, limits how close the detector can be placed. To address this, the IRIS concept proposes a retractable vertex detector within the beam vacuum for ALICE. Sensors can be positioned just 5 mm from the interaction point within a secondary vacuum enclosure that acts like a mechanical iris, retracting during beam injection and extending once the beam stabilizes. A first design targeting aperture, impedance, and alignment requirements has been produced, along with a mechanical prototype. This novel concept pushes the limits of conventional vertex detector designs and opens new R&D avenues for materials, processes, and operation. IRIS is part of the ALICE3 upgrade proposal for LHC Run 5.

As tracking detectors expand outward from the vertex, the growing detection volume presents new challenges in modularity and integration. R&D is exploring modular designs where each module is a fully functioning unit integrating sensors, electronics, mechanical support, and cooling, with industrial scalability in mind. WP4 proposed a module concept based on a ceramic 3D-printed substrate (but also more standard carbon substrate have been studied) with embedded cooling channels. These modules can be interconnected in a LEGO-like fashion through plug-and-play interfaces for both mechanical and hydraulic connections. The benefit of maintaining full functionality within each module is the ability to fully characterize the final module before it is assembled into the detector, as well as the ease of replacing individual units. However, this approach introduces additional complexity due to the increased number of hydraulic interconnections. For this reason, a new reliable in plane hydraulic interconnection has been developed and fully qualified.

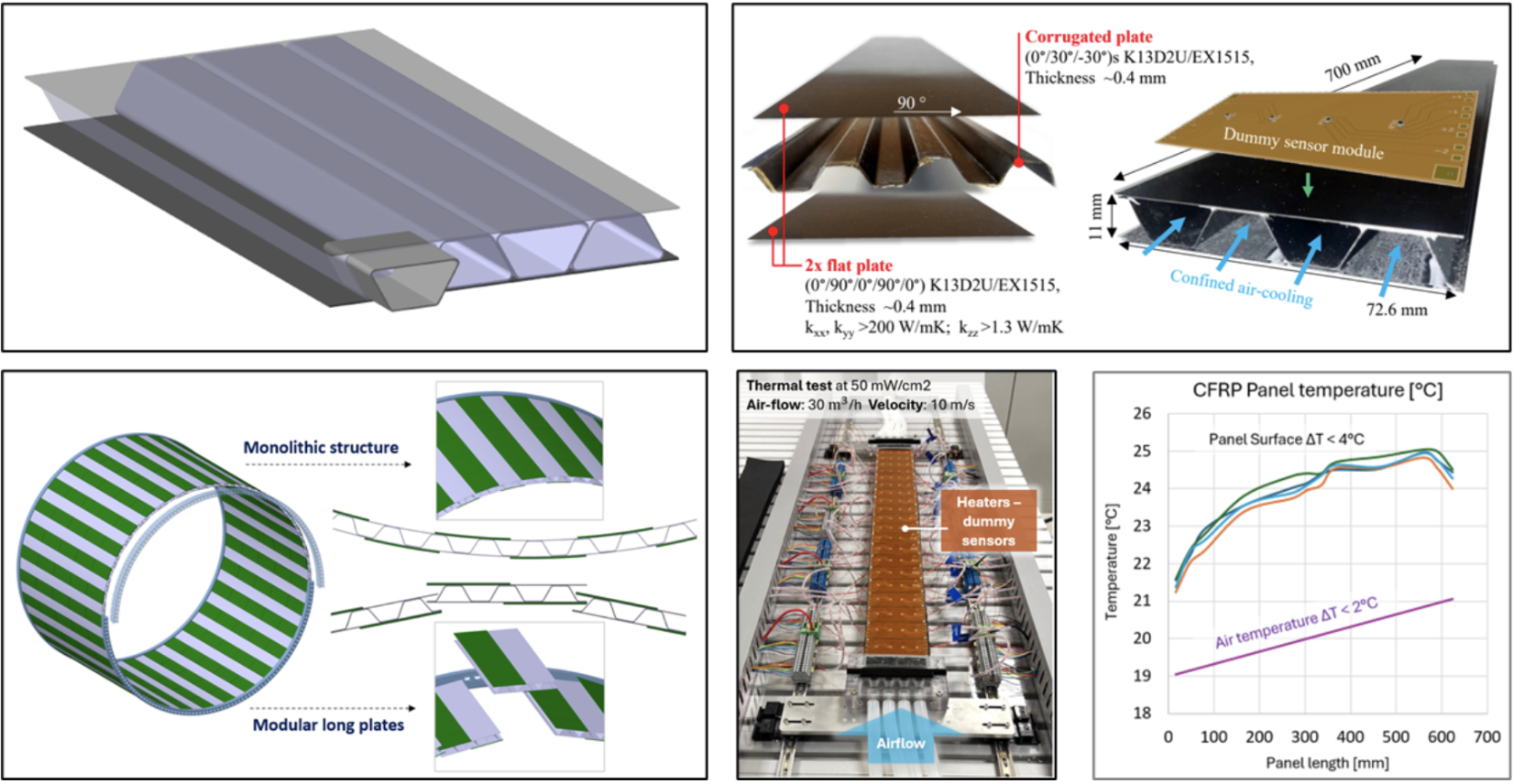

In lower-power, low-radiation regions, R&D is exploring how liquid cooling can be replaced by air also on large-scale detectors. Corrugated carbon-fiber sandwich structures supporting the sensor serve both as mechanical support and as air ducts. The air channels are integrated within the sandwich itself, acting as both the structural core and the cooling ducts. Using high-thermal-conductivity fibers (e.g., K13D2U), these CFRP sandwich plates achieve excellent rigidity while maintaining an ultra-low material budget. Airflow within the core integrated channels effectively removes heat from the sensor on the sandwich skin, eliminating heavier liquid-cooling systems. Thermal tests with 30 m³/h airflow at 10 m/s and 50 mW/cm² heat load show temperature rises of ΔT < 4 °C along the plate and ΔT < 2 °C in the air, confirming uniform and efficient cooling (Fig.3).

Figure 3 – CFRP corrugated sandwich plates for sensor support and air cooling of large surface tracking system with thermal test setup and temperature profile along the panel length.

Superconducting Magnets and Calorimeters

Moving radially out from the tracker, material-transparency optimization remains a key consideration also for the outer calorimetry. A superconducting magnet is typically located in the transition region between the tracking system and the calorimeter, or immediately after the calorimeter, and is conventionally housed in metallic cryostats for thermal insulation. Although considerable effort has been made to reduce the thickness of superconducting coils, the cryostat itself remains a major source of material, impacting the outer calorimeter. In the case of liquid-argon calorimeters, an additional cryostat is required, and in some designs, such as ATLAS, a single cryostat is shared between magnet and calorimeter.

Replacing the current aluminum-alloy cryostat with a fully carbon-fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) design is the primary R&D goal, aiming to enhance structural transparency by reducing material budget up to 60%. This development is inspired by carbon-composite tanks for aerospace launchers, even if requirements are slightly different.

The design is driven by several key requirements, including leak-tightness for both vacuum and liquid argon (in the case of a liquid calorimeter), thermoelastic stability, long-term radiation hardness, structural integrity at cryogenic temperatures, and the ability to accommodate large dimensions. Carbon composite materials with a thermoset resin system and filament winding processes have been used for the first engineering assessment and are now being compared with thermoplastic composites made via automated fiber placement. Two different thermoset resin systems have been tested: CTD-7.1 (used in aerospace applications) and LY556 (commonly used in cryogenics). These resins offer the potential for tougher materials that, combined with thin-fiber-ply technology, improve leak-tightness. On the other hand, thermoplastic composites offer long-term radiation resistance and the ability to join carbon parts through thermoplastic welding. Three thermoplastic systems are currently under evaluation: carbon-fiber LMPAEK, PPS, and PEI. While these materials provide superior radiation resistance and stability, they require processing temperatures in the range of 300–340 °C, compared to 130 °C for thermoset resins. However, this remains well within the capabilities of current industry processes.

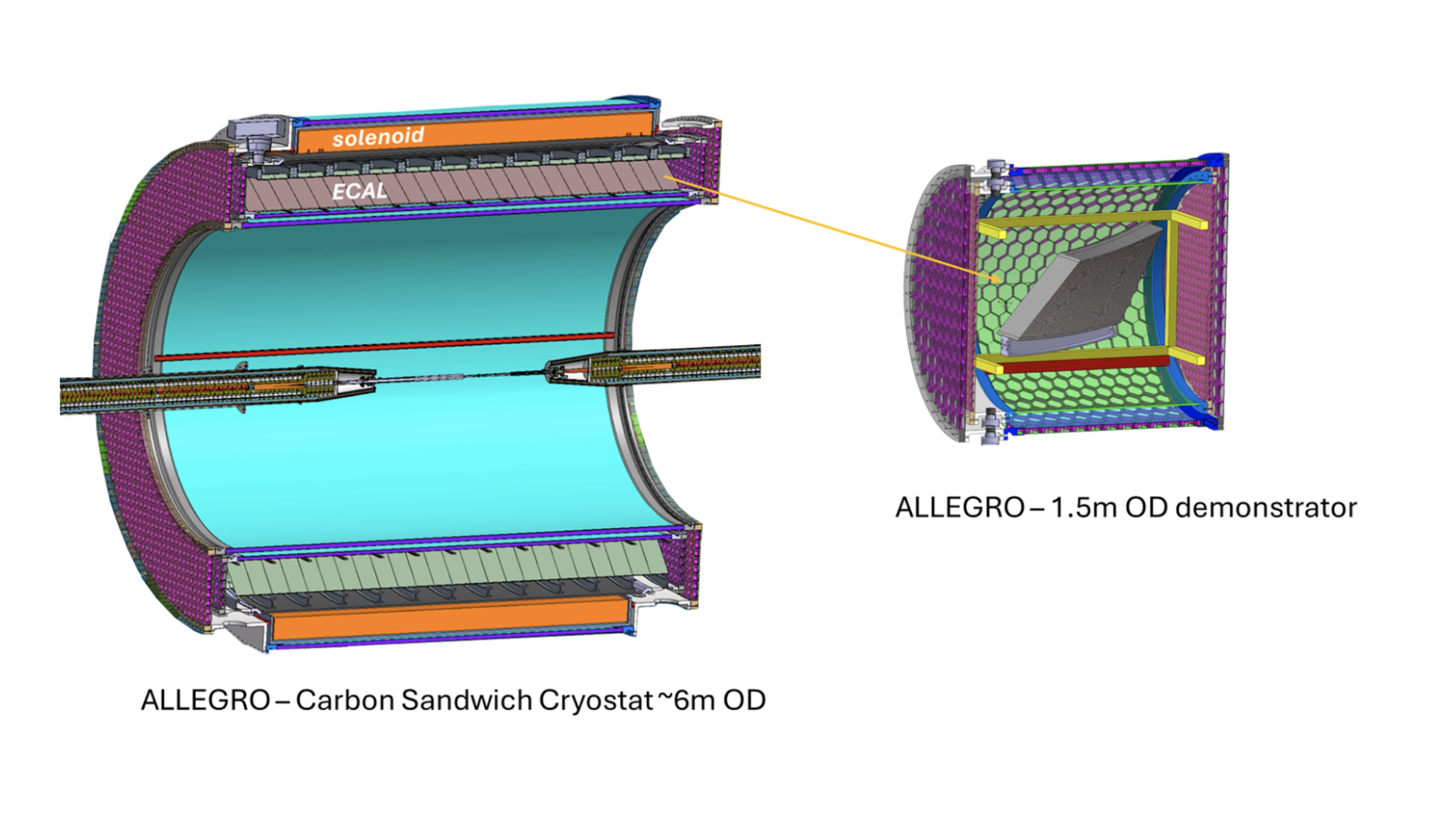

As a case study, the ALLEGRO detector for FCCee, designed to house both the ECAL barrel and a surrounding solenoid magnet, is under study by the R&D group. A preliminary design for the main structural shells and connections has been released. The design focuses specifically on carbon composite production instead of metal, addressing significant engineering challenges due to its large size and the combined cryogenic and structural loads. The next phase will focus on comprehensive materials characterization, utilizing a 1.5-meter diameter demonstrator in synergy with WP2, with the aim of supporting the Calorimeter demonstrator (Fig.4).

Figure 4 – ALLEGRO Carbon Fiber Sandwich Cryostat: A large-scale cryostat design tailored for carbon manufacturing will be validated through a scaled demonstrator.

Automation and Robotics in Detector Infrastructure

The R&D is not only focused on the detector's mechanics but also on improving its deployment and long-term operation in the experimental cavern. As particle detectors grow larger and more complex, automating tasks such as installation, inspection, maintenance, and disconnection becomes critical to improve safety and efficiency and reduce personnel radiation exposure. To address these needs, robotic systems are being developed to handle detector modules during setup and removal, significantly cutting down the manpower required for these operations.

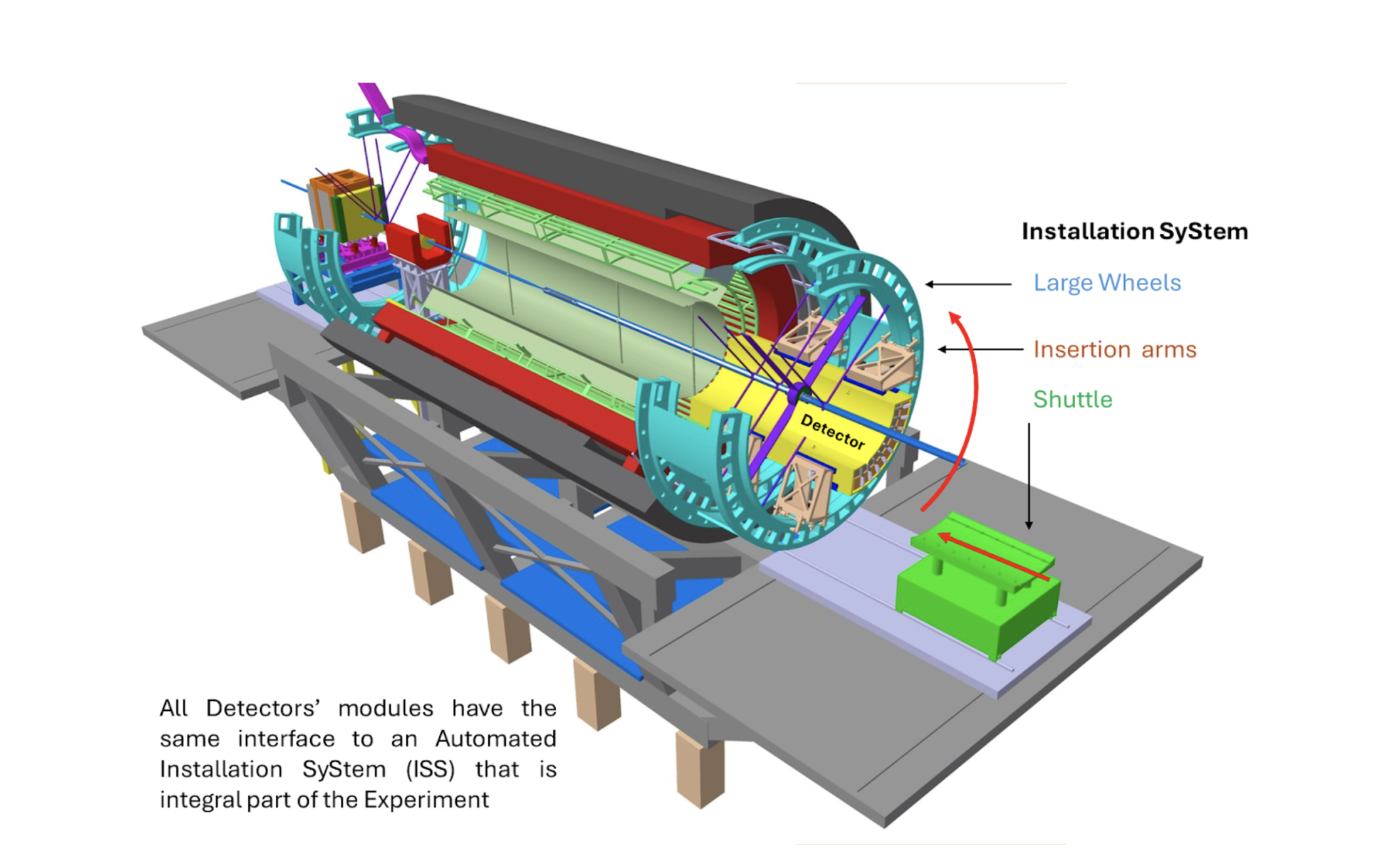

A key outcome from ongoing research is the importance of designing detectors with robotic compatibility from the beginning. This includes developing standardized mechanical interfaces, simplified connection and disconnection mechanisms, and modular architectures that facilitate robotic operation. A case study developed within the R&D group, for the upcoming ALICE 3 experiment illustrates this approach: each detector module, whether barrel or endcap, is designed with a common-design mechanical support shell and a unified interface for installation, enabling a single robotic system to efficiently handle the insertion and extraction of all different detector types.

Figure 5 –ALICE 3 experiment, highlighting a modular design approach in which all detector units share a common standardized installation interface, allowing a single robotic system, integrated in the Experiment, to insert and extract the full range of detector types efficiently.

Although fully automated detector handling is not yet implemented in experimental caverns, similar methods have already been used in space. For example, the new 3-meter-diameter silicon-strip layer upgrade for the AMS experiment on the International Space Station (ISS) will be installed entirely by robotic systems. This inspired the adoption of the same strategy for its surface handling: an ABB IRB-8700 robotic arm has been acquired, instrumented, and programmed for use in the test beam at CERN for layer calibration, before being transported aboard SpaceX’s Dragon capsule. In the test beam, the robotic arm will manipulate the detector and autonomously perform scanning trajectories.

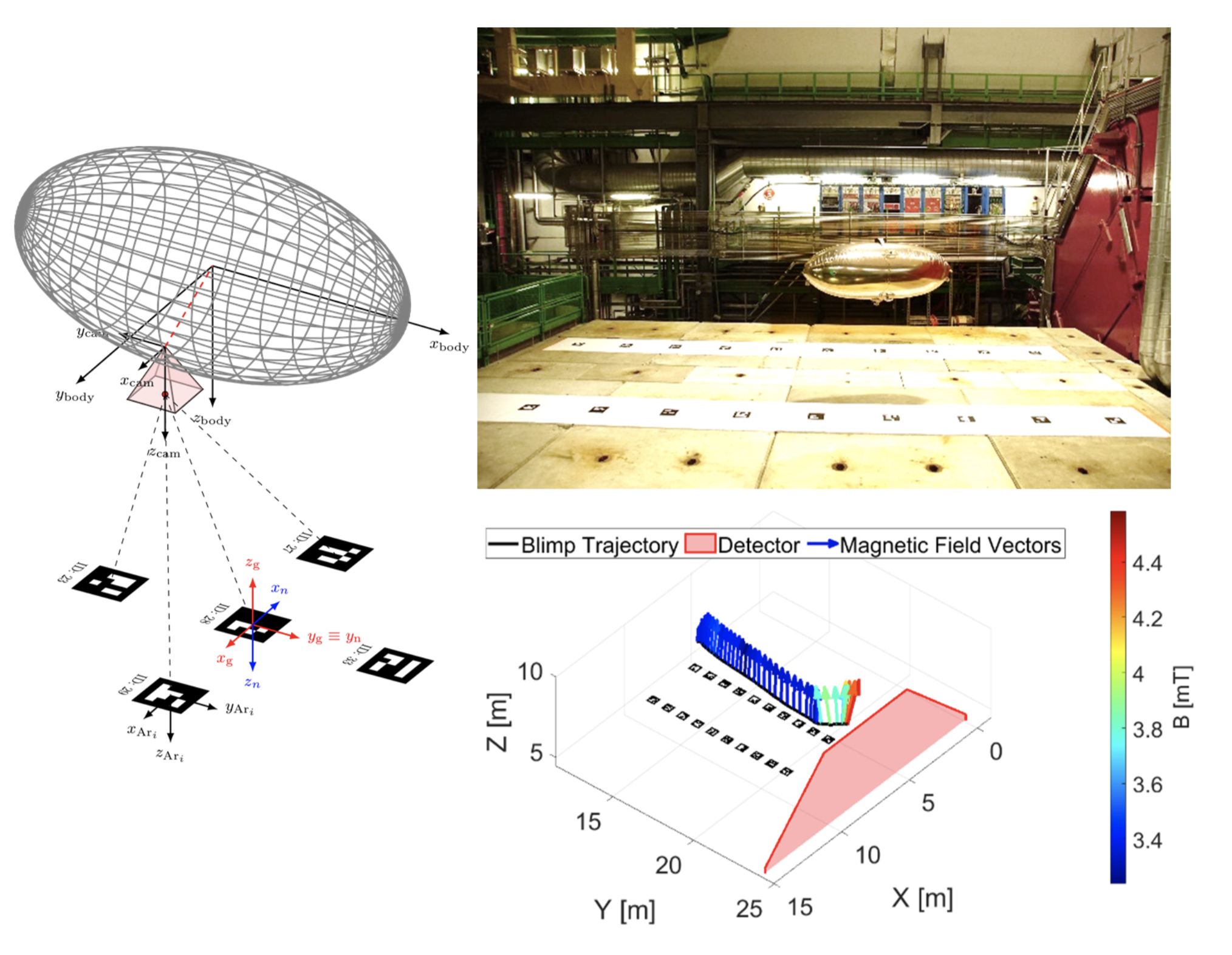

In addition to large robotic systems for module handling, efforts are underway to develop autonomous robots for inspection. Quadruped robots like the UNITREE Go1 and ANYmal are being tested for their ability to navigate irregular terrain, climb stairs, and avoid obstacles. Robotic swarms, consisting of miniature units, are being explored for accessing confined or obstructed spaces, leveraging mobile mesh networks for reliable data transmission. Aerial platforms, such as blimps, are also being developed for 3D mapping and inspection of delicate detector components (Fig.6). These robotic systems integrate cameras, radiation sensors, magnetic probes, and navigation tools for precise mapping, helping improve the overall automation of detector installation and maintenance.

Figure 6 – Navigation of blimps inside an experimental cavern (ALICE) , operating near magnetic fields, for environmental inspection and mapping

In summary, significant progress is being made within EP R&D WP4 in both detector mechanics and handling concepts. On the mechanics side, the focus is on achieving an ultra-low material budget while ensuring excellent mechanical stability, minimizing impact on particle trajectories, and enabling high-precision tracking moving closer to the Interaction point. Innovative cooling solutions are being developed, such as air cooling for lightweight design and Krypton-based cooling for areas with higher radiation loads, all while adhering to strict structural constraints. At the same time, a new concept for detector handling during installation and maintenance is being developed. This concept introduces a single, universal installation jig that supports insertion, extraction, and maintenance across all detector types, eliminating the need for multiple dedicated tools and interfaces.