Transfer-induced fission at the ISOLDE Solenoidal Spectrometer

How are the heaviest elements in the Universe formed? Looking at the periodic table, we know where the lightest elements come from. Hydrogen and helium were forged in the primordial nucleosynthesis that took place just moments after the Big Bang. Elements such as lithium, beryllium, and boron are mainly produced by cosmic-ray spallation, when energetic particles collide with heavier nuclei in the interstellar medium. Heavier elements up to iron were synthesised later through stellar nucleosynthesis.

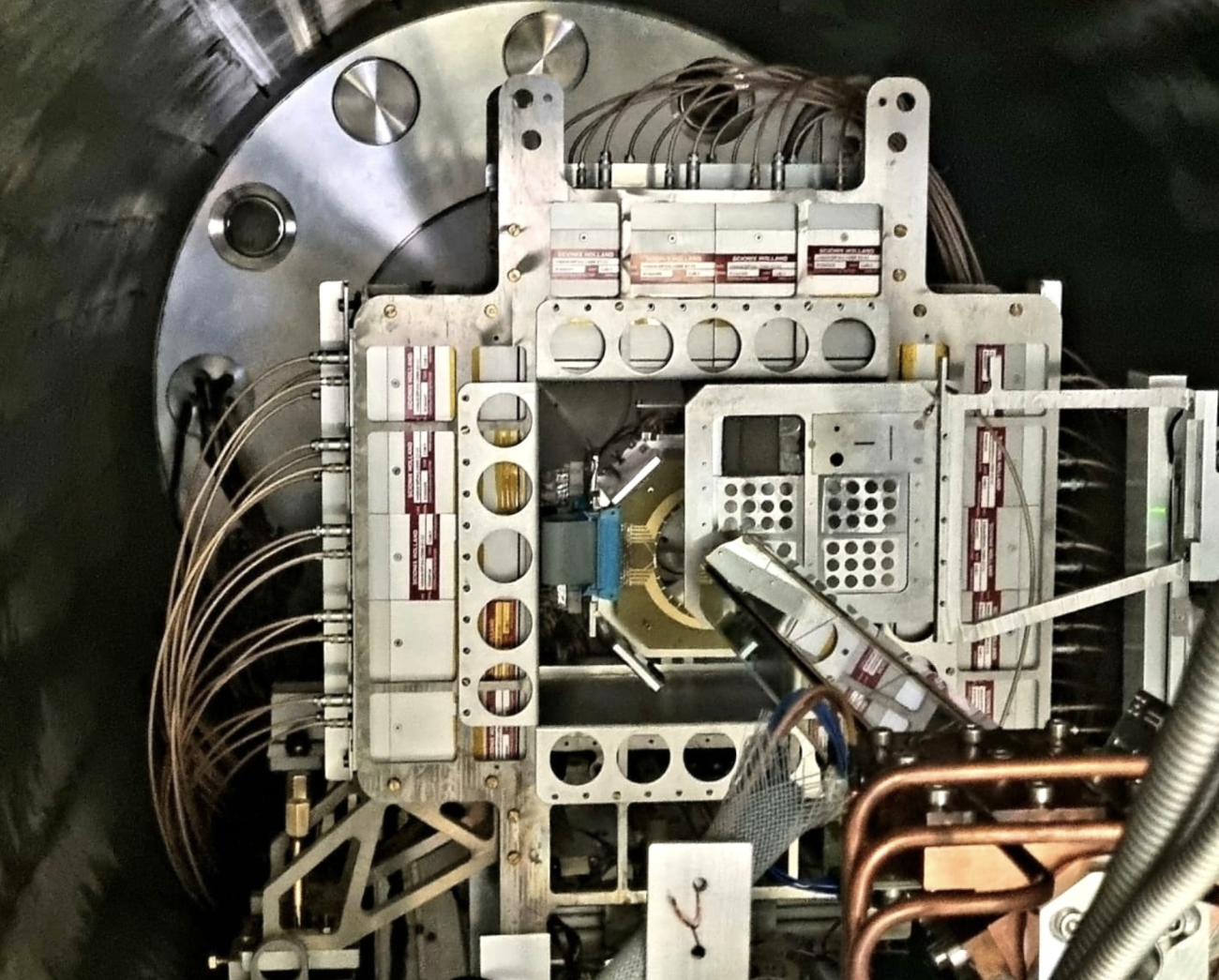

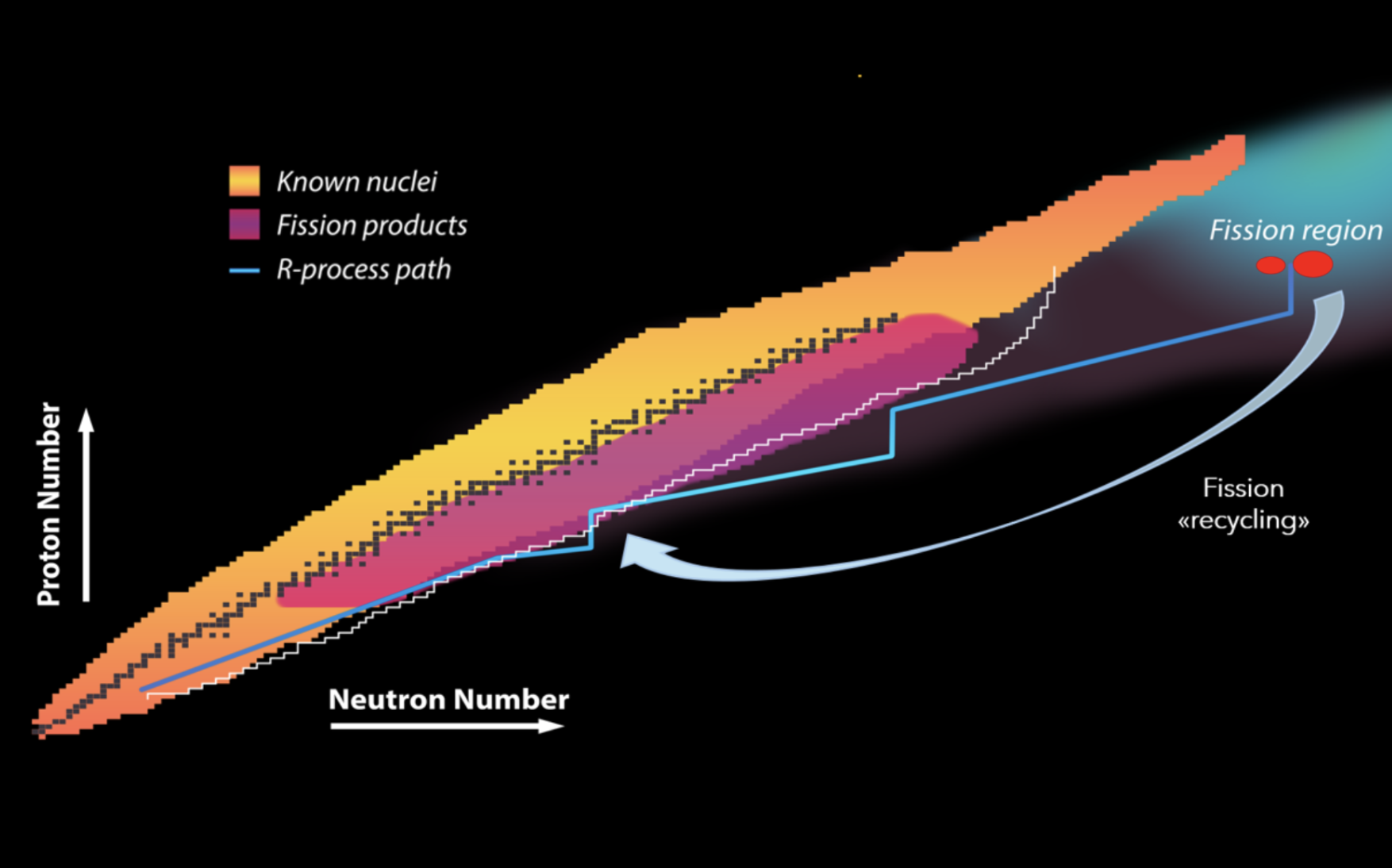

But what about the heaviest elements in the periodic table — gold, uranium, and other transuranic nuclei? Their origin lies in some of the most extreme astrophysical environments, such as neutron-star mergers, where an enormous flux of neutrons triggers the rapid neutron-capture process (r-process). Through successive neutron captures and beta decays, this process builds up nuclei far from stability, eventually producing the heaviest elements we find on Earth (Figs. 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Nuclear fission limits the mass of nuclei, which can be produced in the r-process. The two fission fragments will again undergo neutron capture and β−decay, thereby contributing once more to the r-process. Adapted from an image by © Matthew Mumpower (2007-2025).

In principle, the r-process could continue indefinitely, producing ever heavier nuclei. However, extremely neutron-rich nuclei can split via fission, returning lighter fission fragments to the r-process. This so-called fission recycling plays a key role in determining the final abundances of heavy elements. Studying nuclear fission of neutron-rich nuclei can therefore address key questions, such as where the r-process ends.

Yet, our knowledge of fission in these exotic systems is extremely limited. The nuclei of interest are highly unstable and cannot be used as targets for traditional neutron-induced fission measurements, if they can be produced in the laboratory at all. At ISOLDE, a new method has been developed to learn more about the role of fission in the r-process.

Traditionally, fission barriers are determined by bombarding a fissile nucleus with neutrons or charged particles of known energy. While this works well for stable or long-lived nuclei, investigating short-lived species requires alternative experimental strategies.

The ISOLDE facility can provide neutron-rich radioactive beams of interest, which are further accelerated using the HIE-ISOLDE post-accelerator. The beam can be directed onto a deuterated carbon (CD2) target, where it can interact via the (d,p) transfer reaction. In this reaction, the neutron from the deuteron is transferred to the beam nucleus, increasing its mass number by one, while the proton is ejected. By measuring the energy of this proton, we can determine the excitation energy of the newly formed isotope. Measuring the fission probability as a function of the excitation energy then allows us to extract its fission barrier.

Figure 2: Artistic impression of a neutron star merger (© Mark Garlick / University of Warwick)

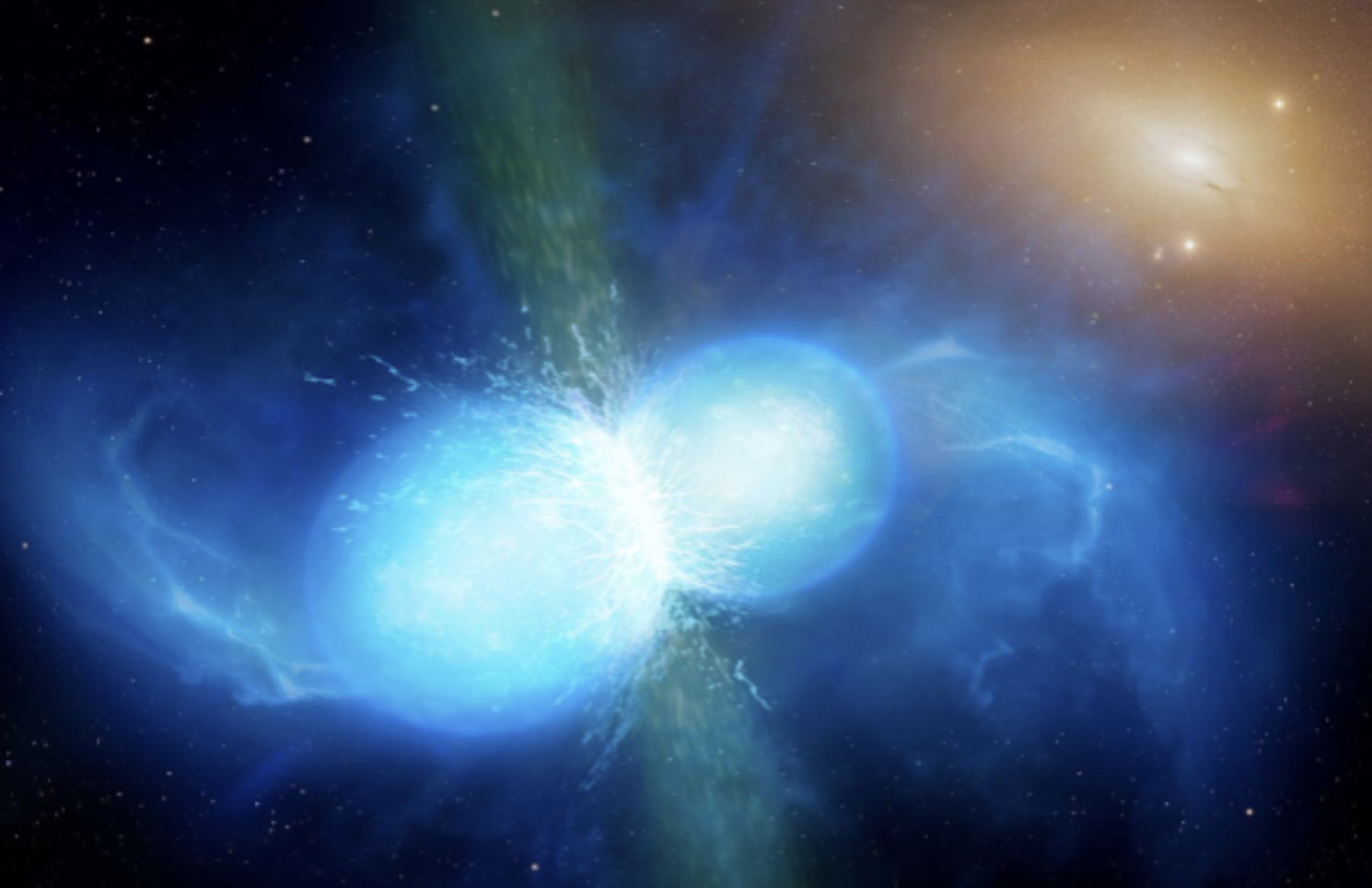

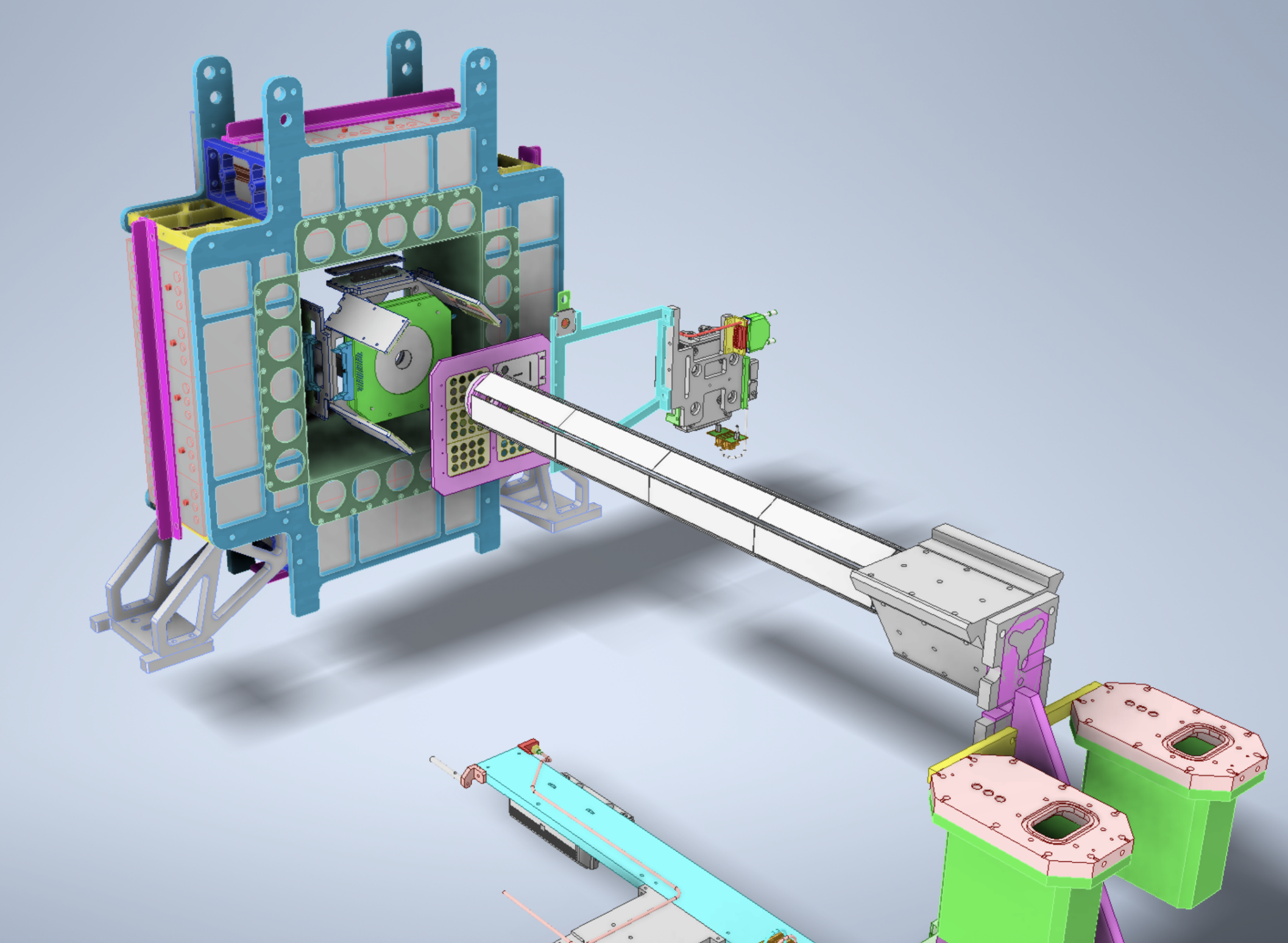

As a first proof-of-principle experiment, we studied in July 2025 the known radioactive nucleus 233U, via the 232U(d,pf) reaction. For the measurement, we used the ISOLDE Solenoidal Spectrometer (ISS) (Fig. 3). It features a large, 0.9 m diameter superconducting magnet that provides a 2 T uniform magnetic field. The CD2 target was placed inside the magnet and surrounded by detectors used to measure the outgoing proton, the two fission fragments, and gamma rays emitted during the reaction. The magnetic field cleanly separates the reaction products and enables excellent energy resolution.

Figure 3: Schematic picture of the solenoidal spectrometer principle. The accelerated beam enters from the left in the superconducting solenoid. The position sensitive silicon detector array in the upstream direction, three typical helical proton trajectories and a recoil after a reaction in the target are indicated. Figure adapted from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:B12_schem.png

The combination of HIE-ISOLDE capabilities and the innovative ISS setup provides worldwide unique experimental conditions.

Figure 4 presents the detection setup inside ISS. The detection system includes an on-axis position-sensitive silicon array – protons follow helical trajectories in the magnetic field and strike the detector when they return to the magnet's central axis. Fission fragments were detected using double-sided silicon strip detectors in a dE-E configuration, while gamma rays were detected using an array of 28 CeBr3 crystals arranged around the target. In addition, four silicon luminosity detectors measured deuterons back-scattered from the target, allowing the total number of incoming 232U ions to be determined.

Figure 4: Schematic illustration of the setup used inside the ISS magnet, beam enters the setup from the right.

Data analysis is ongoing, but the first results are very promising. In the future, we hope to apply this technique to neutron-rich nuclei – bringing us closer to understanding how the heaviest elements in the Universe are created.