Tips for a better virtual experience

A year ago, as the first reports of COVID-19 infections started to reach us from China, it was almost certain that none of us really foresaw the impact that the pandemic would have on our lives and on high-energy physics as a field in 2020. As things became more and more serious, and the epidemic started to gain ground in Europe, we gradually realised that none of the events we had planned for the Spring and early Summer of 2020 would be able to take place in their intended face-to-face formats. Communities and organising teams started to scramble to think what to do. Some events were just postponed into the future, as even then we hoped that maybe we would be over the worst of COVID-19 by the end of 2020, instead of finding ourselves in the midst of the second European wave. As the impact and timescale of COVID became more evident we started to rethink our assumptions and see, for workshops, conferences and training events, what could be realistically achieved online. Even if it wasn’t an online event that we wanted, it became obvious that in many cases an online event would be better than no event at all.

One of the first events that was held in a purely online format was the WLCG-HSF workshop in May 2020, which had originally been planned for Lund. The first problem we encountered when deciding to go virtual was to decide what time of day we could actually schedule the event. We’ve all been to conferences where half the delegates are wandering about in a jet-lagged haze, but with a bit of acclimatisation and liberal dosing with coffee people soon adjust to the new location. But with an online event we could not avoid the fact that the Earth is round and that we wanted to engage with our colleagues worldwide, in Asia-Pacific, Europe and the Americas. Anyone working in ATLAS or CMS will know that the best answer (or least bad one) is the golden meeting slot, 16-18h, in the late afternoon at CERN and mid to early morning for America (very early for the Pacific coast). As we were a relatively concentrated community in HSF-WLCG we had to accept that the time was pretty awful for our Asia-Pacific colleagues. At larger events, such as ICHEP, where it was necessary to be even more inclusive, a set of sessions that ran in the morning for Europe, but caught the afternoon for Asia. So if you’re organising an event be mindful of this.

Photo from the November WLCG-HSF workshop

The second major choice was which platform to choose to run the event in. CERN’s Vidyo service had significant scaling issues in the first days of safe-mode running at CERN and Zoom had been hurriedly brought into service. The security of Zoom was a concern, but following some advice from IT and improvements inside Zoom itself, we felt it was good enough for our purpose. The platform now seems to have become the de-facto standard for our community, as well as many others, and with pretty good reason. It generally copes well with scaling up to large events (up to 1000 in conference mode and even more in webinar mode). No wonder it will become the standard offering at CERN next year. The little touches, such as the “raise hand” feature, enable meetings to be run far more smoothly than when people just have to speak up - everyone knows that a few hundred milliseconds of lag can easily lead to two speakers tripping over each other, speaking and pausing together, like two polite people trying to pass one another in the street. So we went with Zoom and didn’t regret it. In those early days and we did have a few false starts when people were still figuring out the platform, but one thing that helped us a lot was opening sessions in advance and allowing the presenters for the session to test their setup and connection.

As humans we can only process one stream of audio and video at a time, but one of the joys of workshops are the little side conversations that we have. We found that some system where people can chat is a much better multiplexer as it’s possible to focus on the particular conversation of interest while multiple can, in principle, happen at once. Chat in the conferencing system, like Zoom, isn’t really a good solution here - there’s only one thread, no “quoting” and the whole conversation will disappear in a puff of electrons when the meeting is closed. So save that chat for immediate issues with the meeting, like a audio stream failure. For the scientific discussions in workshops a shared Google Doc, in which everyone can write, is a great option. Just make sure that people writing comments identify themselves [e.g., your name in brackets - Graeme S] and that the document is pre-laid out with a section for each of the presentations or topics so people know where to write. While it can be frustrating to be reliant on third parties there isn’t really another tool that’s quite as easy to use and with which people feel immediately at home. Tools like Mattermost can also be used, e.g., with a channel for each parallel session at a conference. This is more structured, which can be less confusing, but also more limiting, so you have to just the pick one that’s best for your community.

Another good thing to do is to make sure that speakers upload material in advance - having it a day before can help participants to review the material and even pre-ask questions in your workshop notebook. That helps a lot to make sure that discussion is focused on the most interesting topics and it also allows people who are in unfriendly timezones to contribute to the discussion. We also found it extremely useful to record all of the live discussion in that notebook so that it serves as a record of the workshop and can be used to identify follow-up items. So have a rapporteur who takes care of that.

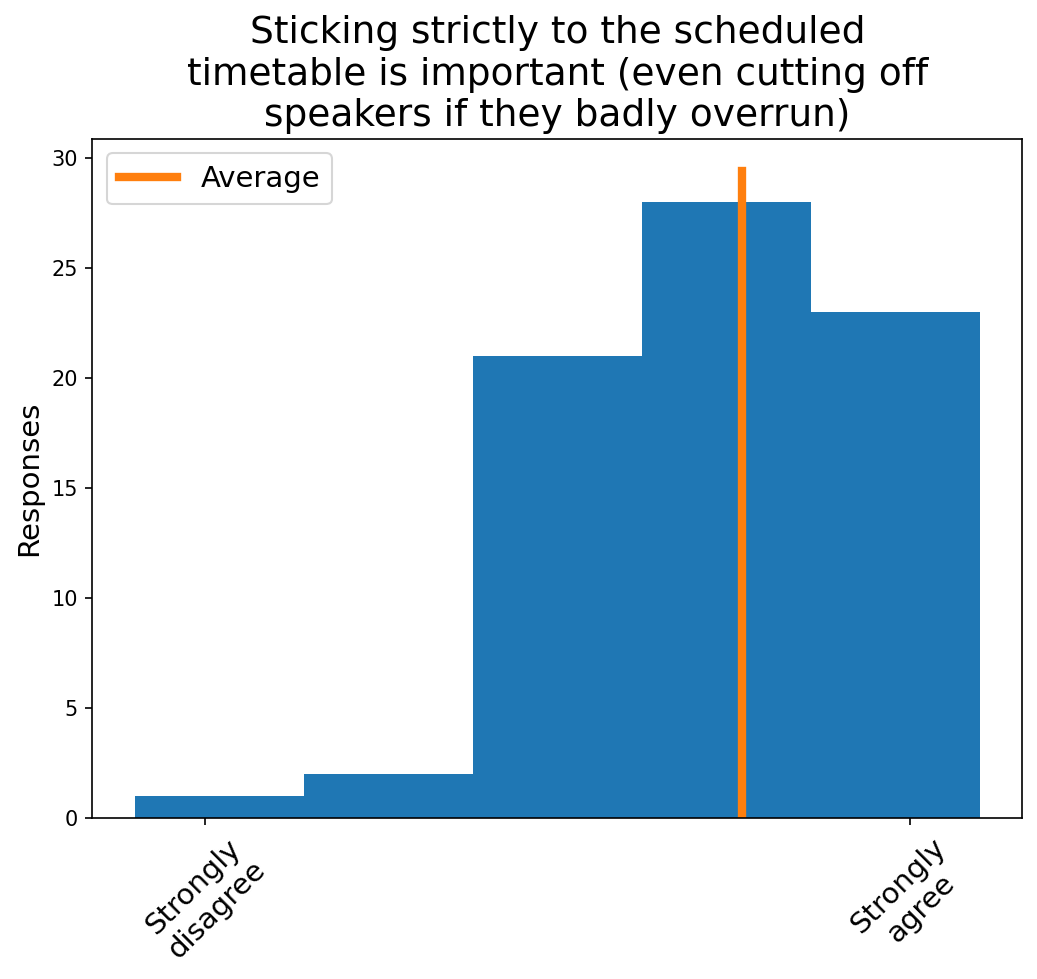

Discipling your speakers to upload their material in advance is one job for the organisers; another one, for the chair in particular, is to make sure that speakers stick to time (and this time I mean it…). This is even more important in virtual meetings as participants may be interleaving their attendance with other meetings and activities. In the HSF workshop people told us that they would rather have speakers stopped in their tracks than to allow the schedule to slip. Particularly in a workshop environment, discussion time is probably the most valuable element, so don’t let that get swallowed up by ill-disciplined speakers who go on too long. With adequate preparation speakers can communicate their key ideas even in 10’ talk slots and save the extra details for backup slides.

Keeping track of speaker’s times, workshop notebooks and a meeting chat channel is a lot of work for a chair. Assign a deputy chair to help out and point out anything the chair might have missed. It’s also a good idea to have a deputy who can step in if, during the session, the chair’s internet connection decides to go AWOL - yes, it has happened. All of the organisers should have an out-of-band chat channel (something like CERN’s Mattermost is absolutely ideal). This clearly helps in organising the workshop, but shines for things that crop up during the session where an instant message chat is indispensable as email is just too slow.

If your event’s sessions last a long time then you must schedule breaks. It’s hard for participants to focus on virtual meetings for long stretches and the reality is the meeting is competing with everything else happening on a participant’s laptop: email, chat, news alerts. Two hours on the go is probably a real upper bound without a break. A three hour session should have at least one break, maybe two. The PyHEP workshop ran light-hearted straw polls (what’s your favourite Matplotlib colour palette?) on Slido during their breaks and that also helps to give a gentle restart into the session.

Finally, after the event, it can be a great thing to upload recordings of the talks. Zoom can record the session directly, then there are many simple open source tools to split the video up into one file per talk. Remember our poor Asian colleague for whom it was 3am when the workshop finished? They will thank you for being able to watch the talks and discussion at a more sociable time. Right now on Zoom get a few people to record (just in case someone’s connection dies), but “cloud recording” should become a more reliable option soon. It’s imperative to get everyone’s permission to record and publish the talks so advertise this well and even add it as a checkbox at registration. Adding the talks to Indico and CDS allows them to be found easily and some communities, like HSF, have their own YouTube channels which offer nice playback features.

Following all of these practical tips can really help a virtual event to be a success. Hosting the event can be something that the community really benefits from and running it smoothly and effectively is a responsibility that the organisers have.

Of course, there is, unfortunately, still a major piece that’s missing. It’s the coffee queue interaction, the quick chat in the lobby, the invitation to continue the discussion at dinner. This is a huge part of the perceived value of our events - particle physics is a scientific endeavour, but with a huge social dimension to it and the community has suffered the lack of this in 2020. Some attempt has been made to host virtual drinks (bring your own bottle) and, while not without merit, none of these have really been a big success. Neutrino 2020 hosted a VR poster session, which was very impressive, but the technology felt immature. It may be that this aspect of virtual interaction has to wait for another leap in platform development or technology (after all, a VR headset is less than a transatlantic plane ticket).

Neutrino 2020 avatars The conference's poster session took place in virtual reality. Credit: M. Del Tutto / Fermilab (Originally published in the CERN Courier).

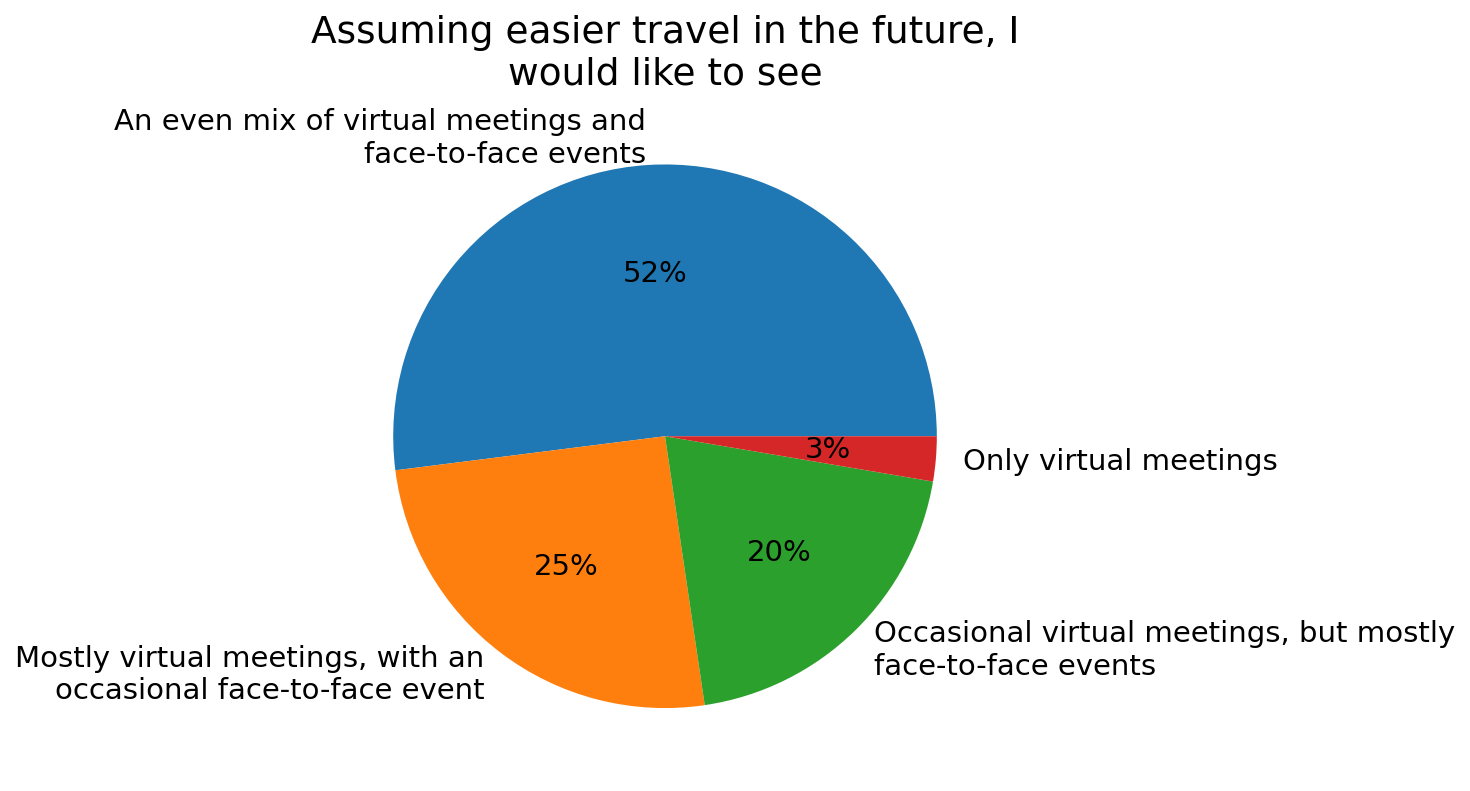

Even with this aspect lacking though, virtual events have matured and become increasingly successful throughout the year. We should also not discount two significant advantages to events of this kind either. First, there is effectively no financial barrier to participation, so colleagues may be able to join us when previously lack of travel budget might have prevented them - particularly for younger people or less affluent institutes this is a boon. Secondly, the environmental impact of virtual events is practically nil compared to flying 1000s of physicists around the world. Reducing the environmental impact of our travel, at least for some fraction of our meetings, is something we should seriously consider, even after the COVID pandemic passes, as a way of making our professional lives more eco-friendly. I am sure that this was a factor in people’s thinking when we asked what kind of events they wanted to see after the WLCG-HSF workshop and the most popular option by far was to mix some virtual workshops with face-to-face events. So at least part of our future looks like it should continue to be virtual!

The pie chart shows the responses from participants of the WLCG-HSF workshop on the kind of events they wanted to see in the future with most popular option being a mix of virtual with face-to-face events.

Virtual Workshop Checklist

-

Pick a time of day that works for your community’s timezones

-

Have slides uploaded in advance (at least a day)

-

Have a workshop notebook for comments both during and outside the session times

-

Make sure speakers stick to time and guard your discussion slots

-

Support the chair with a deputy and a rapporteur - make sure the organisers have a chat channel for running the sessions

-

Have breaks to let people rest from concentrating on the meeting

-

Record the meeting and upload the video for posterity and people in other timezones